Sporting Artist C.D. Clarke Creates Alaska’s Outdoor Scenes Via His Paintings

The following appears in the February issue of Alaska Sporting Journal:

BY CHRIS COCOLES

Asporting artist who has painted outdoor scenes and portraits throughout the globe, C.D. Clarke couldn’t ask for a better setting than Alaska to craft an epic piece. At least when Mother Nature cooperates.

“The only thing that works against Alaska – and everything else is positive about Alaska in terms of creating outdoor paintings – is the weather,” Clarke says. “Doing watercolors in the pouring rain doesn’t work out very well. And fog isn’t that interesting to paint.”

But on a good day in the Last Frontier, it’s a land Clarke would want to break out the brushes to capture a place so rugged, so full of wildlife and fish, colors and landscapes. “You couldn’t ask for a better place to do what I do,” he says.

“It’s inspirational; in terms of the sort of storytelling side to my work in trying to share these incredible experiences with my viewers, it’s just perfect, and the scenery is often incredibly dramatic,” says Clarke, who will turn 65 on March 14. “Lots of interesting compositions. It has everything. What’s not to like?”

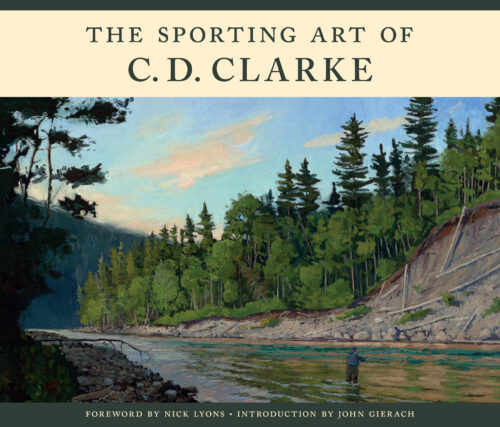

Certainly, Clarke’s visits to Alaska have been among many life-changing moments. Others include taking art classes from a dedicated high school teacher in his native Rochester, New York; mentoring from a much older cousin who’d become a famous artist; and time spent traveling the country and globe flushing birds and casting for fish. All inspired his work, and a new book, The Sporting Art of C.D. Clarke, celebrates his life through it (see excerpt below).

Clarke, who likes to say he was born to paint, fish and hunt, always wanted “to have a record of what I’ve been doing for the better part of my life.”

Having created book cover illustrations and contributing to several publications, his contacts in both the media and marketing industry provided avenues to getting something done. But it was a dinner party at his home a couple of years ago that began to make such a project a reality.

“A client of mine … said, ‘How come there’s not a C.D. Clarke book?’” he recalls. “Unless you’re Ansel Adams, they’re not big moneymakers.”

But it’s been more “magical,” as Clarke puts it, than monetary, to reflect a wonderful career with painting tools.

“I was in the middle of a dream coming true. ‘Holy smokes; this is actually going to happen’ … It just reinforced the feeling that I often have about how lucky I’ve been to do what I’ve been able to do,” hesays.“Thereareafewpiecesinthere that are really old – like 35 years ago. And so looking back was great. It’s also kind of neat to be able to take a look back when I’m not completely over the hill yet. I look back on all the places I’ve been, and some of these remarkable places I’ve been to many times.”

That certainly includes the Last Frontier.

CLARKE’S PATH TO ALASKA started in, of all places, Chile. He’s been a regular visitor to South America, home of some outstanding fishing and hunting opportunities. He says he’s been to Argentina about 15 or 16 times and is planning a bird hunt there in 2025.

But on a whim, he was once invited to a Chilean fishing lodge owned by Jim Repine, a legendary outdoorsman on multiple continents. Repine eventually settled in Chile, but years before that he was something of a folk hero in Alaska, where he wrote books, edited magazines and hosted the TV show Alaska Outdoors.

“Back in the day, Jim Repine was Mr. Alaska,” Clarke says. “He had the first outdoor TV show in Alaska. And it was him flying over in a small plane with his Rhodesian ridgeback named Jubal.”

In Chile, Repine, who passed away in 2009 at 76, and Clarke became fast friends, and the former invited the latter to fish in Alaska as he headed north every summer to toss a line.

On one such Last Frontier adventure, Clarke found himself in one of those spots that anglers dream about, casting for trout in the Brooks River, home of big rainbow trout and bigger brown bears that also are there to pursue those same fish.

“I landed my first-ever Alaska rainbow. It wasn’t a gigantic rainbow by Alaska standards. But it was probably 6 pounds or something like that,” Clarke says. “A nice fish, for sure. But for a kid from upstate New York, I’d never seen anything like that. It was absolutely amazing.”

That memory was even more special when another fisherman holding court upstream came down and asked the newbie if he wanted a photo with his prized catch.

“He could tell I was really excited. He takes a picture, and unlike most of the time when someone tells you he’ll send you a picture, this guy actually did,” Clarke says of Mark Emery, who just happened to be an outdoor filmmaker and cinematographer who Alaska Sporting Journal correspondent Bjorn Dihle once referred to as the “Most Interesting Man In Bristol Bay” (ASJ, February 2021).

Such a special moment only reinforced Clarke’s newfound love of Alaska.

“There was a (Brooks) bear that they called Diver because he had learned to literally float downstream from the falls and grab salmon underwater. He would tip up like a duck. And I can remember this bear. The scary thing about that was he’s floating down the river,” Clarke recalls. “So it’s not like he’s walking down the river. He’d suddenly appear, and the river’s not that wide. Here was this bear and he’d be 15 feet in front of you floating down the river. I certainly remember him.”

There would be many more critters, fish and scenes to inspire Clarke’s artistic urges over the years.

GROWING UP IN ROCHESTER, New York, Christopher David Clarke had a passion for fishing. His dad and grandfather were both fishermen, so C.D. would join them whenever he could.

“It was smallmouth bass and panfish, and even at a very young age I was passionate about that kind of stuff,” he says. “I can remember my grandmother — my mother’s mother – had a cottage at one of the Finger Lakes, and all I cared about was fishing. She said to me, ‘You know, you can’t fish all the time.’ And as wise a woman as she was, she got that wrong.”

Hunting soon followed when C.D. was a teenager and his dad allowed him to have a gun. And while the outdoors was a passion, high school proved to be the spark of a career that combined Clarke’s obsessions.

Tom O’Brien was his art teacher, and Clarke had an idea that it would be more than just the basic elective class many students take.

“I did a little bit of painting and drawing as a younger kid, but high school is where it got a lot more serious because of this phenomenal teacher, Tom O’Brien, who ran a very serious art program. He sent several people onto professional art careers, which is amazing for the high school level,” Clarke says.

“He was just one of these Energizer Bunny kind of guys to begin with. He was a pretty talented painter himself.”

Indeed, some of O’Brien’s work was displayed at Rochester’s local art museum, and his teaching methods had an impact on Clarke. Students would pose for portraits in class – “obviously clothed; we didn’t want to have half-naked bodies with a whole bunch of high school kids,” he says with a laugh.

“I’ve always said from the very beginning, if you can draw the human figure, you can draw anything. It’s by far the most difficult thing to draw well. And to start students out at that level was amazing.”

O’Brien also would put his budding artists in a circle in the classroom and surround them with objects to paint.

“There were wagon wheels, kind of classic white eggs on a white tablecloth. There were flowers and all kinds of stuff. That just got you used to looking at texture, looking at color, and that you had to take pieces of this and put it together into something that was interesting to look at,” Clarke remembers. “So he was just working on all the fundamentals that every art student needs to work on. And I just don’t think that most high school- level classes go at it that seriously.”

It was in Mr. O’Brien’s class where Clarke painted his first legitimate piece of sporting artwork. His canvas featured a self-portrait that included one of his many beloved dogs, a Brittany, holding up a pheasant they hunted together.

The artist himself was wearing a hunting outfit – “my grandfather’s beat-up old canvas hunting coat and a tweed hat.”

“I sort of want to say it’s awful, but also not too bad for high school,” Clarke says. “I’m very proud of that … For a high school kid to even try a portrait – and it’s pretty good-sized and probably half my size – that was really swinging for the fence. That’s probably a good demonstration of the fact that I was into this outdoor stuff.”

He’d attend nearby Syracuse University, which has a fine art program, but downstate in New York City, Clarke would also learn a lot from a family member more than five decades his senior.

ALBERT K. MURRAY WAS in the U.S. Navy during World War II and commissioned as a lieutenant of the Combat Art Section. Besides serving for the Navy’s Fourth and Eighth Fleets during the war, he sketched battle scenes and painted portraits of Naval war heroes such as Admirals Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and William “Bull” Halsey.

Murray (1906-1992) became an in- demand portrait artist who also painted the likes of astronaut and U.S. Senator John Glenn and members of the high- society Rockefeller and Mellon families.

A second cousin Clarke always referred to as “Uncle Al,” Murray went far in the art world. Fourteen of his paintings hung in Washington D.C.’s National Portrait Gallery.

“By the end of his life he had three or four people who wanted their portrait painted waiting in the queue. So he never needed to organize a show or needed to be published in a magazine. He had more than enough work,” Clarke says. “He was an amazing guy.”

One day, when Clarke was in college and visiting Uncle Al in Manhattan where he lived, they were walking through Central Park after checking out an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Out of the blue, Murray mentioned something that stuck with Clarke.

“He said, ‘I want to tell you something: If you completely dedicate yourself to your work and work really hard, I can not guarantee that you’ll be famous. But I guarantee that you can make a solid living. And you’ll have the most interesting career you can possibly have.’”

That someone else in the family had become a successful artist was something of a turning point. In Sporting Art, Clarke muses that his parents never said, “No one makes a living as an artist.” And here was Murray imploring his cousin to stick with it and that it could become a fascinating professional ride.

Profitable or enough to get by, it would never get boring.

“Nobody ever said truer words to me. And it certainly proved to be true for me. But in terms of artistic mentoring, I was at the very beginning of my career and I don’t think I can say the second year of art school is the beginning of your career,” Clarke says.

“And he was at the very, very end (of his). I didn’t get to spend any brushing time with him; I didn’t get to do critiques with him; I wished the hell that our careers overlapped by 10 or 15 years instead of a couple of years. Most of my time with him I was a little kid. I was not an artist yet and he was a famous painter.”

Murray was artist buddies with two fellow iconic New Yorkers, illustrator Dean Cornwell and painter Ogden Pleissner, the latter of whom Clarke calls “one of the most famous sporting artists ever.”

“Al had written a letter to Ogden Pleissner saying that, ‘I have this young relative who is starting off on much the same path as you and has the same interest in sporting art and painting hunting and fishing. He’d love to meet you sometime.’”

Sadly, Pleissner was in London at the time and died of a heart attack in 1983. The meet and greet never came to fruition. “The letter was waiting for Pleissner at his studio in Vermont and he never got it. So a near miss with one of my idols,” Clarke says. “Apparently, Pleissner was kind of a curmudgeonly old guy, so it may have been a horrible experience.”

TWO OF CLARKE’S FAVORITE Alaska-based paintings reflect what the state typically means to outdoorsmen and -women, plus sporting artists alike.

“One is the painting called ‘Two Silvers.’ The general principle of showing a bright fish and a dark fish, and then the fact that I had that green background – I forget whether it was a dock or a deck – the whole idea of putting a red fish on a green background. Those being complementary colors, the whole thing kind of came together,” Clarke says of the watercolor painting. “You had one fish facing one way and one the other. It was one of those things that almost painted itself from the concept. And I think it was really effective.”

Clarke titled his other favorite Alaskan work “Jet Boats.” It’s an oil painting that depicts an overcast scene on a Last Frontier river. He says Alaska’s beauty can be shown in more subtle ways. Yes, there are snow-capped mountains glistening in sunshine, the kind of environment that would make painters salivate to create. But the jet boats represent something else entirely.

“For me anyway, it kind of captures that rugged, cold, misty side of Alaska. As an angler and outdoorsman I love that kind of weather. So many of my greatest experiences have happened in that kind of weather. If you’re really serious about the hunting and fishing stuff, you’re not always looking for bright sunny days,” he says. The 49th state’s weather may change in a blur, but you can create something magnificent in every condition.

“The concept of those having two or three little splashes of color with the gas tank and the life vests, that was one of the things that drew me to it. Everything in that painting is sort of gray and mossy green, except those splashes of color. That kind of works from a purely painting perspective.”

He’s been to Alaska a half-dozen times now (Clarke’s wife Tracey often joins him on many trips these days, along with their bird dogs, as she’s become a diehard bird hunter). He’d love to go back and experience a float down a river, perhaps in Southeast Alaska targeting the steelhead run. Think of the potential such a journey could inspire for a painter who’s created moments from similar adventures in Argentina, Canada, Scotland and more.

Clarke cites famous sporting artist Robert Abbott, who once said, “You’ve got to paint the football before you paint the stitches on the football.”

Clarke takes such advice to heart, citing that the football stitches represent the idea that such personal touches are “all about the details.”

“When you look at it from a sporting art lens, the thing that you absolutely have to do is to look at it as a painting first. And that means that you gotta have a painting that has an interesting composition and has some interesting colors and interesting textures. You can’t get hung up on the fact that everyone says a river is a beautiful river; that’s kind of the literary product,” Clarke says. “Anything like that has to come after you’ve determined that it’s going to make a good painting in terms of the nuts and bolts of composition and color and design.”

In the book’s foreword, noted fly angler and author Nick Lyons talked about Clarke’s gift expressed through his paintings.

“Many remind us of places we have been, experiences we have had afield or astream, sights we have seen, but his paintings are never photographic,” Lyons writes.

“C.D. also offers the crucial moments for sportsmen – the moment of a strike or the bent rod in the midst of the fight; these could easily become a cliché in sporting art, but they always seem alive and real in C.D.’s paintings.”

As Clarke reflected on the book’s release and his years of hard work, travel and painting his life onto canvas, he became sentimental about how he evolved as a craftsman of color.

“When you have extreme passion coupled with extreme talent, that’s when you get the few geniuses that are out there. That’s when you get a Picasso or a Mozart. Or a John Singer Sargent, where you’ve got an incredible facility built in, plus the passion to keep doing it,” he says, citing Sargent as one of his inspirations.

“I think most artists out there in any of the arts, not everybody is a genius, but there are lots of people who have produced great art and written lots of great music who aren’t geniuses. You’re not going to do the hard work if you don’t like doing it. That’s why I think passion is the important thing. I had the passion part right from the beginning. And that’s what kept me doing it a lot. Because I loved it.” ASJ

Editor’s note: For more on C.D. Clarke and to order a copy of his book, go to cdclarke .com. You can also order The Sporting Art of C.D. Clarke at Amazon and elsewhere.

SIDEBAR: C.D. CLARKE ON HIS ART INSPIRATION

Editor’s note: Here’s an excerpt from The Sporting Art of C.D. Clarke, published by Stackpole Books and reprinted by permission:

After graduating from art school, I moved to a very rural part of Maryland’s Eastern Shore and tried to figure out just how I was going to make a living as an artist. (Albert K. Murray’s) wise words had not been specific and figuring out a plan proved to be key to more than just paying bills. I worked all kinds of part-time jobs to keep my head above water – everything from planting trees in newly clear-cut forests, to riding a garbage truck, to waiting tables, and I had to also figure out how to keep painting.

I developed a new skill that would become an important part of my art career. I taught myself to paint quick watercolor paintings, on location, en plein air. At the time I lived on Chesapeake Bay and there was an endless supply and variety of subject matter right outside my door: Old wooden workboats, picturesque crab shacks and salt marshes stretching to the horizon required no effort to find. I could come home from work, grab my painting gear, and be painting immediately. I painted hundreds of watercolors (and tore most of them up), learning my craft the only way you can learn to paint: by painting a lot.

Unfortunately, I did not sell a lot, so I continued with the many part-time jobs for at least 10 years. I did, over time, get better at watercolor, throwing fewer and fewer away, and eventually some of the better ones were noticed. I had a painting published on the inside back cover of Gray’s Sporting Journal.

I was invited to show in the Gold Room at the Easton Waterfowl Festival. I met collectors of sporting paintings who owned salmon camps, houses in the Florida Keys and ranches in Montana. They encouraged my coming to their special places and painting on the spot, creating a piece that was uniquely of their place and not just a generic painting of salmon fishing or bird shooting or trout fishing out west. My career was finally starting to take shape.

From the very beginning I have insisted that my paintings be works of art and not just representations. By this I mean that compositions, colors, shapes and values must work together in a pleasing or intriguing way in their own right. In other words, it is not enough for a painting of an apple to look like an apple. It must be a good painting of an apple, an interesting rendering of an apple, that says something about the apple. One of the ways I try to achieve this is to let the paint have a say in the painting. How the paint is applied, the freshness of washes in watercolor, and the texture of the paint in oils are important to achieving the result I want. I suppose that this is the reason I have chosen to work in a more impressionistic style than many of my contemporaries. This style was much more the norm in the sporting art of the past, but as with much of representational art in the second half of the 20th century up to the present, reliance on photographs has had an impact …

What an incredible adventure it has been. Never in my wildest dreams could I have imagined that I would paint and fish and shoot in all the remote, exotic and exclusive locations that have been my pleasure to experience around the world. Patagonia, Alaska, Christmas Island, Labrador, Belize, the Bahamas, the Scottish Grouse moors, salmon rivers both sides of the Atlantic (Restigouche, Moisie, Teed, Spey, Sela, even Alta). All have been incredible, and I hope there are more to come.

These amazing destinations inspire me to continue to improve my craft. Ogden Pleissner is quoted as having said, “It (painting) always lets you down. There are very few pictures that I have done that I think are just great. That I don’t have to do something more with.”

I do agree, but somehow that hasn’t made me want to give up. I believe that the next painting is going to be the best and I stay encouraged. Though the next painting might not be the best, I feel that my work is still improving, and I hope I never get to the place where that is not the case. C.D. Clarke