Restoration Due The Eklutna: Ensuring Salmon Access Necessary

The following appears in the March issue of Alaska Sporting Journal:

BY ERIC BOOTON

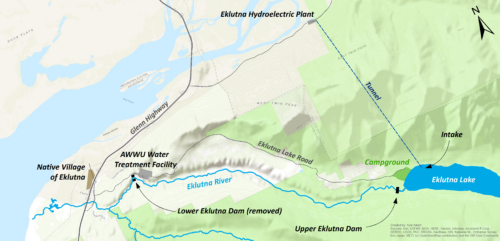

In 1929, a 70-foot-tall, 100-foot-wide concrete dam was built blocking the journey of all five species of wild Alaska salmon to their native spawning grounds. In 1955, a second dam was built on the river roughly 8 miles upstream at the outlet of a lake, so every drop of water could be diverted through a nearby mountain and out a hydroelectric power plant.

This is the brief modern history of the Eklutna River – traditionally known as Idlughetnu – a glacier-fed stream just northeast of Anchorage. It likely comes as little surprise to you, but after losing access to habitat and the flow of water, wild salmon of the Eklutna have suffered immensely. The Dena’ina Eklutna peoples who the river has supported since time immemorial have also lost a significant source of food and cultural tradition.

When the second dam was built on the Eklutna River, the downstream lower dam was abandoned. In 2018, more than 60 years later, Eklutna, Inc., The Conservation Fund and the Native Village of Eklutna successfully removed the defunct dam, knocking down a significant hurdle for wild salmon and setting the stage (Alaska Sporting Journal, April 2021) for fish to return to their upstream home once again.

However, since no water is allowed to flow past the dam at the outlet of Eklutna Lake – causing the river to run dry – and even if there was water there would be no way for fish to swim past that remaining dam, Eklutna River salmon still face serious obstacles.

FORTUNATELY FOR FISH, THE utilities that operate the Eklutna Hydroelectric Project are required to make up for their impacts on fish and wildlife. Unfortunately, it’s not clear the utilities are willing to do enough. The mitigation process is in its earliest stages. The Eklutna River Restoration Coalition, which my organization Trout Unlimited contributes to, is committed to ensuring the outcome results in a fish-filled Eklutna River that the Dena’ina Eklutna peoples, and all Alaskans, can be proud of.

Last year was the second and final year of utility-led field studies that are supposed to inform decisions about what mitigation measures will be required to make up for the project’s impact on fish and wildlife.

Although questions remain about whether the studies were adequate, later this year the utilities plan to offer up a draft mitigation plan for public comment and review, before sending the plan off for final consideration by Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy in 2024.

Beyond the utilities’ studies, biologists for the Native Village of Eklutna are also researching the river, including conducting fish population and fish habitat studies. Following the removal of the abandoned lower Eklutna dam, village biologists found salmon are moving further up the river system than they have in the past.

Gravel is being transported throughout the system, improving fish habitat by creating new gravel beds for spawning. New scoured-out pools are providing holding areas for returning adults. New side channel habitat, which is important rearing areas for juveniles, has been created. Streams flowing into the lake – upstream of the remaining dam – likely also provide significant potential salmon spawning and rearing habitat if only fish could migrate in and out of the lake.

Most excitingly, Chinook, chum and coho adults were all observed above the confluence with Thunderbird Creek for the first time in several years, charging their way forward through barely a trickle of water in an otherwise dry riverbed. Following the removal of the abandoned lower Eklutna dam, the river is healing, fish habitat is being rebuilt, and the salmon are responding. But these fish still need adequate water in the river and passage around the remaining dam to truly return home.

After nearly a century, resolution is inching closer for Eklutna River salmon. But it still remains unclear whether the operators of the Eklutna Hydroelectric

Project – the Municipality of Anchorage, Chugach Electric Association and Matanuska Electric Association – will seize the opportunity to adopt meaningful mitigation measures that will allow wild salmon once again to thrive in the Eklutna River.

TO ILLUSTRATE THE CHALLENGES Eklutna salmon face, as well as demonstrate the commitment of the coalition working to bring salmon back, the CEO of Eklutna Inc., Eklutna Inc. board members, Native Village of Eklutna tribal leaders and other volunteers walked, ran and biked two salmon from Native Village of Eklutna to Eklutna Lake, nearly 11 miles up a winding mountain road.

The arriving salmon were met with the support of more than 100 community members who walked the final leg of the relay and lined up to pass the salmon one-by-one, person-by-person, up and over the dam and into Eklutna Lake where salmon belong.

“This area has been used by our people for well over 1,000 years. It is our hope that one day, within my lifetime, we will see all five species of salmon make it from saltwater up here to the lake,” Native Village of Eklutna president Aaron Leggett stated during a speech at the Return the Salmon relay.

It’s clear the Eklutna River, and the wild salmon attempting to swim home, need water and a way to swim past the remaining dam. Alaskans have made it clear they expect the utilities to uphold their end of the bargain. Anything less will fail to meet moral and legal obligations.

In September 2022, Anchorage leaders echoed resolutions of support previously passed by the Native Village of Eklutna and the Alaska Federation of Natives. The Anchorage Assembly passed a resolution that commits their support for providing instream flow and fish passage, and requests that utility operators commit as well. This resolution passed with sweeping bipartisan approval.

Still, at the time this piece was being written, the Municipality of Anchorage, Chugach Electric Association and Matanuska Electric Association continue to drag their feet and remain unclear about their commitment to restoring the river and its salmon. Ideas such as piping water miles downstream before releasing it into the dry channel, “trapping” returning salmon downstream of the dry river and trucking them around the dam, and other inadequate proposals from the utilities would barely be Band-Aids compared to more meaningful solutions, such as allowing a fraction of the available water to flow naturally and bypass channels around the dam that have proven effective elsewhere and deserve study here.

The impact of dams and hydroelectric development on the Eklutna River is plain as day. Blocking fish passage and dewatering the river have diminished formerly flourishing salmon populations. The basic requirements to repair the harm are equally clear: return flowing water to the Eklutna River and construct a mechanism to allow salmon to migrate up and down past the dam. Now is the time for the Municipality of Anchorage, Chugach Electric and Matanuska Electric Association to show leadership, own their impact in earnest and adopt a meaningful mitigation plan that makes up for the decades of impacts.

For Eklutna salmon advocates, 2023 will culminate with the release of a much-anticipated draft fish and wildlife plan outlining the utilities’ proposal for how salmon may one day return to the Eklutna. Alaskans will get the chance to comment on and provide input into the plan. I’ll be there in support of fish passage and water for the Eklutna River, and I know I won’t be alone. ASJ

Editor’s note: Eric Booton is the Eklutna project manager for Trout Unlimited’s Alaska Program. Conserving and restoring fish habitat is his 9 to 5 gig; chasing wild fish is his summer and fall pastime. The Eklutna River Restoration Coalition is comprised of Native Village of Eklutna, Eklutna Inc., Trout Unlimited, The Conservation Fund and The Alaska Center. Learn more at EklutnaRiver.org.