Remembering The Maine, Remembrance On Memorial Day

Nobody is more of a history geek than this editor whenever he travels. If there’s a battlefield, museum or monument nearby, I want to see it. I’ve visited Civil War sites near Nashville and a Revolutionary War battlefield around Greensboro, North Carolina. In Greece I saw a memorial for locals murdered by Nazis and even a German cemetery honoring paratroopers killed during the invasion of Crete. I took my time walking through the Museum of Occupation in Riga, Lativa, a country that suffered horribly at the hands of not just Hitler but also Stalin.

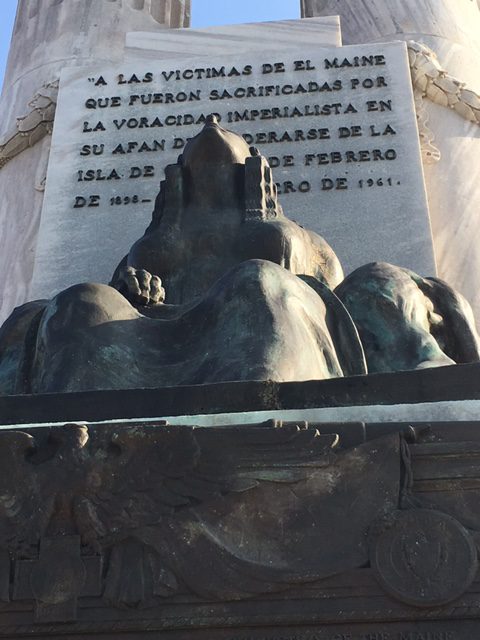

So when I went to Cuba in late March and early April (I’ll have a feature on Cuba’s adopted son, famed American writer/fisherman Ernest Hemingway, later this year), I wanted to make sure I got a history lesson while I was there. While I learned so much Cuban history and found some perspective about a very complicated nation, it’s funny that I had to be reminded by our tour guide about our country’s pre-Castro connection with Cuba. “That’s the U.S.S. Maine memorial,” she told us as we sped in a 50s-era Chevy along the iconic Malecón, the wide boulevard that separates Havana from the Atlantic.

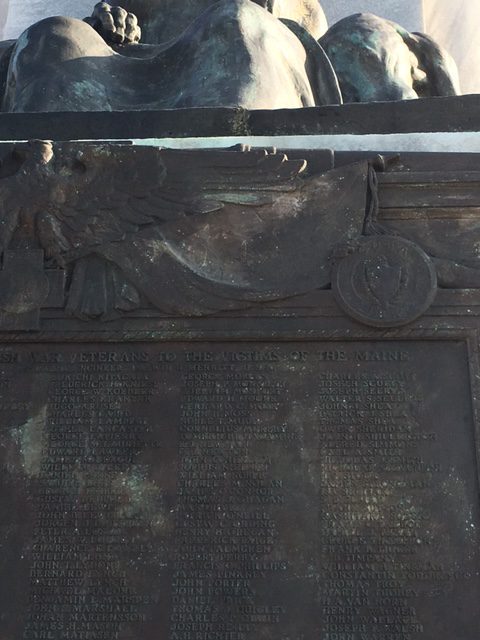

We must have driven back and forth between that statue five times during our (too) short Cuban trip, and I kept wondering if I’d have time to see it. We did so much walking around Old Havana, including one night strolling on the waterfront, but we never had a chance to actually walk the Malecón. So on our last day as we headed back from Playa Girón (site of the infamous Bay of Pigs invasion), I asked our very friendly guide and our driver if we could make a quick stop so I could take a quick peek at the Maine monument. It was a very significant moment in both American and Cuban history.

Exact Date Shot Unknown

Here’s more from PBS:

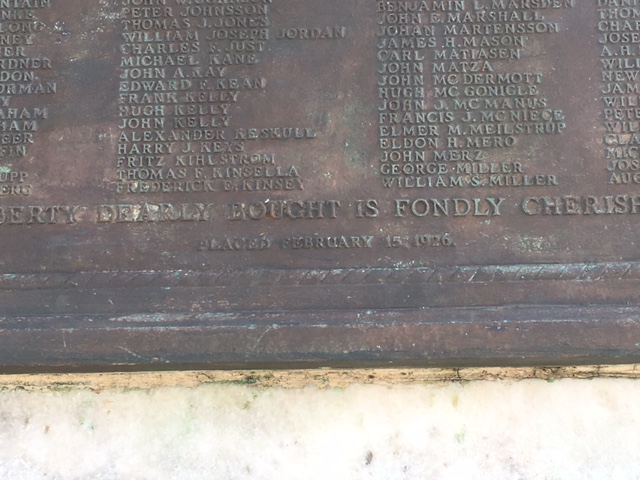

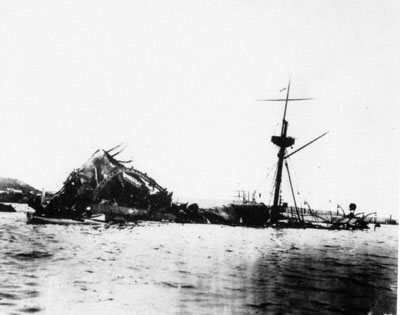

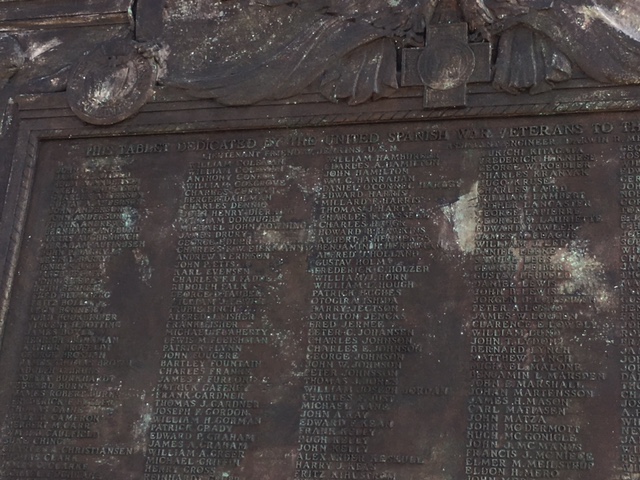

At 9:40pm on February 15, 1898, the battleship U.S.S. Maine exploded in Havana Harbor, killing 268 men and shocking the American populace. Of the two-thirds of the crew who perished, only 200 bodies were recovered and 76 identified.

The sinking of the Maine, which had been in Havana since February 15, 1898, on an official observation visit, was a climax in pre-war tension between the United States and Spain. In the American press, headlines proclaimed “Spanish Treachery!” and “Destruction of the War Ship Maine Was the Work of an Enemy!” William Randolph Hearst and his New York Journal offered a $50,000 award for the “detection of the Perpetrator of the Maine Outrage.” Many Americans assumed the Spanish were responsible for the Maine’s destruction.

Of course, the Spanish-American War was the byproduct of the tragedy of the Maine and the sailors who perished in Havana Harbor. A little more about the famous “Remember The Maine” battlecry and ramifications of the explosion, via Historytoday.com:

No one has ever established exactly what caused the explosion or who was responsible, but the consequence was the brief Spanish-American War of 1898. American sentiment was strongly behind Cuban independence and many Americans blamed the Spanish for the outrage. The yellow press, led by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, proprietors of the New York Journal and the New York World, took every opportunity to inflame the situation with the exhortation to ‘Remember the Maine’, publicise the alleged cruelties of Spanish repression and encourage a belligerent hunger for action. They were vigorously supported by hawkish senators and the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, who attacked President McKinley for trying to cool the situation down. In the end the government in Spain declared war on the United States on April 24th. The American Congress had already authorised the use of armed force and the United States formally declared war on April 25th. …

As it turned out, the Spanish-American War was a mismatch:

On July 1st, Teddy Roosevelt’s volunteer ‘Rough Riders’, whooping and hollering, helped Negro troopers of the 10th Cavalry to take the San Juan Heights above the city of Santiago, which surrendered on the 17th. The Spanish Cuban fleet, which had meanwhile fled Santiago harbour, was hunted down by American battleships ‘like hounds after rabbits’ and destroyed in four hours. American troops took Puerto Rico a few days afterwards and the Spanish government sued for peace.

Far more Americans were killed by tropical diseases – typhoid, yellow fever and malaria – in the course of the war than fell in battle (roughly 4,000 to 300). When a peace treaty was signed in Paris in December, Spain lost its last colonies in the New World. The United States took the Philippines, Puerto Rico and the Pacific island of Guam, and achieved worldwide recognition as a great power. Cuba gained independence.

To be honest, I was so focused on soaking up the Cuban culture, seeing the Maine tribute brought me back to reality of the connection our country has to Cuba (it’s incredible how much Cold War tension there was between nations that were separated by all of 90 miles).

I knew I couldn’t stay long at the memorial that warm day in Havana. Our guides had to get home and we wanted to head back to our family-owned casa particular, freshen up and get ready to spend one more night in this exciting, energy-fueled city. So I snapped a few photos and then just stopped for a few minutes to reflect about the American sailors lost (the cause of the explosion remains a mystery).

As we celebrate American servicemen and -women lost in the line of duty on Memorial Day, I’m reminded of what they have sacrificed for me and allowed me the chance to visit tributes to the fallen heroes and heroines, even in Cuba.

Enjoy this holiday, but please take some time to Remember The Maine and remember everyone who got us here.