Meet Homer’s Queens Of Kings

The following appears in the March issue of Alaska Sporting Journal:

BY DAVID ZOBY

When a giant Pacific halibut comes alongside a charter boat, captains and crewmembers usually shoot it or use the harpoon – to bring it aboard alive would imperil the customers.

Capt. Chelsea Schmitt loaded her .410 shotgun while deckhand Emily Leggitt held the leader attached to the fish. Clients peered over the rail and marveled at the size of the flatfish. They took photos with their cell phones and crowded

the area. We sat on anchor somewhere near the edge of the Gulf of Alaska, just offshore from Perl Island, some 45 miles from the marina in Homer.

The weather was iffy, so only a few boats of the fleet had made it out this far. We could hear the barks and bellows of sea lions as they basked on the rocks. The occasional humpback whale blew just a few hundred yards away; tall columns of spray hung in the air.

“OK, I’m going to shoot a gun right now,” announced Chelsea. The .410 popped. Quickly, the captain unloaded the gun, stowed it away and helped Emily hoist the 100-plus pounds of halibut over the gunnels. With two gaffs, the diminutive women hoisted the fish aboard. Their Xtratuf boots squeaked on the wet deck. The fish, mottled with brown skin and covered with sea lice, landed on the deck with a solid thud that reverberated through the hull. This was one of the biggest halibut I had ever seen. Its broad tail thumped a few times. But it was mostly over.

“OK, let’s get some lines back in the water,” said Capt. Chelsea. She seemed rather nonchalant about the whole thing. “Once we get all of our halibut we can go for salmon.”

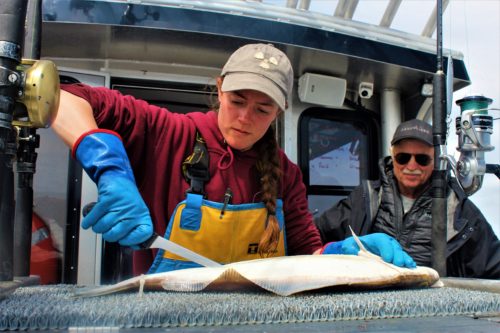

Emily deftly whacked the great fish once with a stout bat. She wasn’t vicious or glib – she was efficient and only wanted to make sure the great fish was dispatched. She bled the halibut with a quick slash to its gills. Then she straddled it and put a yellow tape measure to its length. Halibut are not weighed at sea; rather, their weight is calculated on an onboard chart that uses their length.

It was just shy of 62 inches, which meant it was slightly over 100 pounds. The fisherman, Rick Metzler from Nebraska, was at a loss for words. He had come up with his wife and four grandchildren. A retired cattle rancher, he had only visited Alaska once before, some 25 years ago.

He had gone halibut fishing out of Juneau, but fishing in 300 feet of water, the experience wasn’t what he expected. Here, Capt. Chelsea had parked us in only 90 feet of water. It was easy to feel the fish bite, and to reel up frequently for bait checks and refreshes of cut herring and octopus. Great rafts of bull kelp drifted by. You could hear the surf crashing upon Perl Island. There were kittiwakes and puffins. A tiny gray seabird came to rest near the stern. Emily told us this was a storm petrel and that they come around after nasty weather. She explained that the last few days had been rough and they weren’t able to reach their best fishing spots.

Maybe the rough weather had something to do with this big halibut showing up? But what do I know? I’m a community college professor from Wyoming.

I can say this: This was the greatest fish Rick from Nebraska would ever catch in his life. Even he said so. Somewhere in the fog and surrounded by whale-song, he tried to sum up the experience. He was a little unsteady on the wet deck, his bad knee, the seas rolling a bit from the tide change.

“That fish is beautiful,” he said, finally. “I’m glad you said that,” said Emily. “So many people say halibut are ugly. I think they’re beautiful too.” And though she had just finished the fish off with a bat, when she handled it, she did so with something that looked like gratitude.

CAPT. CHELSEA WILL OFTEN point to the type of charter fishing she does – the day trips out of Homer to catch salmon, rockfish and halibut – as one of the more sustainable methods of feeding oneself a high-quality, organic diet. She compares it to hunting or gardening.

“I think charter fishing is very sustainable. You’re connected to your food – one hook, one line. Being able to catch your fish, and eat it too, is an experience many people haven’t had,” said Chelsea. “And it’s contributing to the economy of a small community.”

Chelsea lived on the Oregon Coast for a period and said she used to go out on her friend’s boat. She was also influenced by her father taking her fishing when she was younger. She said her commitment to fishing has grown, not faded.

Growing up, Chelsea had many people in her family working in the nonprofit world for women’s empowerment and equity. Her parents always told her that she could do whatever she wanted. Chelsea went to college in Oregon and studied International Relations and Conflict Resolution (both useful degrees to have when taking strangers out onto the Gulf of Alaska).

After college, she traveled. Then she found herself in Homer when she heard that the captain of the Irish – not to be confused with the much smallerIrish Mist – needed a female deckhand. The captain of the Irish liked to use two deckhands and wanted to have a male and a female on board.

“I kind of figured I’d try it out for the summer and see if I liked it. Make some money. If I liked it I’d stay. And, if I didn’t, I’d find something else,” Chelsea said.

She took to it, and now has the reputation as a promising captain. She and Emily are often referred to as “The Queens of Kings,” due to their success at catching the highly sought after king salmon. Their names are known at the fish processing plants, at the coffee shops that define Homer, and along the wet boards of the harbor, where the main currency is fish and your reputation for how you handle yourself at sea.

“When I first started coming up here, about six years ago, the only female charter captain I knew about was Aijan,” Chelsea said of Ayjan Arik, the captain of the Bella Vita, which offers half-day halibut excursions. She typically doesn’t use a deckhand.

“She had just gotten her captain’s license. At that time everyone was just sort of deckhanding,” Chelsea recalled.

Today in Homer, there are several female charter boat captains – each with her own specialty. Chelsea and Emily said that the Homer charter community supported them as they were entering the industry. At every step, Chelsea was encouraged to get her license to run a boat. The other captains told her to keep going.

“They are super supportive of females in the fishing industry,” Chelsea said.

MY JOURNALISTIC INTEREST IN Capt. Chelsea and Emily began a few years ago when I heard that Deep Strike Sportfishing had an all-female crew. Alaskan halibut charter fishing is typically a male-dominated profession, complete with bravado, competition and arduous physical demands that are more

closely associated with machismo. (There have always been women in the commercial and recreational fishing industry in Alaska. For example, Capt. Leslie Pemberton from Seward. Pemberton has been involved in commercial and sport fishing since 1974. Today she runs the Tenacious, a 50-foot vessel capable of taking 18 fishers out for

rockfish, salmon and halibut.)

When I first started coming to Homer 20 years ago, there were hardly any women in the charter fleet. The annual halibut derby raised lots of money, but it encouraged fishermen to target and kill the biggest halibut in the ocean, which are always the females, the breeding stock. Back then, there was little talk of sustainability and only taking what you

needed, or what you thought you needed. Even the people on the boats were different in the late 1990s. Halibut fishing tended to be a “guys only” activity. I was part of that. We drank beer. We wore spanking new, puffy camo jackets from Cabela’s. Women, if they were around, were expected to stay ashore and cruise the gift shops on

the Spit. Those days are long gone. Capt. David Bayes, founder of Deep Strike Sportfishing and owner of the Irish Mist, points out that the clientele has shifted over the years. Today, you see more families and children fishing on charters. Though the job is still half brute strength and half customer service, young women are emerging as new leaders in the industry.

In the wee hours of the morning, no less than three female captains greet their customers at Central Charters and head down the boat ramps for a day of adventure. The deckhands, many of them women, grab the bait from a storage shed.

In Homer, it’s not uncommon to see women cleaning fish, running water taxis, piloting planes, and offering whale and nature tours. They wear Xtratuf boots and Grundens rainwear in a fashion trend that could best be described as wharf chic. Homer now boasts female-owned businesses like Salmon Sisters and Two Sisters Bakery, where women call the shots. Chelsea and Emily are part of this sea change; they demonstrate their ability every day when they bring their hauls into Central Charters and hang fish up for photos. And with them comes, perhaps, a longer view. Most days, tourists gawk and marvel at the variety and quality of the fish brought in by the Irish Mist. And they ask the most annoying questions as they stand there in the drizzle.

“Honey, what kind of fish is that?” asked a man with a Texas drawl. The fish cleaner, Delta Fabich, was drowning in fish and had obviously had a long day. She still had to hang two more boats’ worth of fish. So I answered the man myself. I told him that the fish was a Pacific halibut. We were, after all, in Homer, Alaska, “The Halibut Fishing Capital of the World.” Didn’t he see the sign on the way in?

And let me be completely upfront: I was also interested in fishing with Chelsea and Emily because I enjoy filling my freezer with wild fish that I caught myself; though I hail from the catch-and-release school of fly fishing, I love living off what I catch, even if I must admit that I couldn’t do any of this without charter companies.

Captains like Chelsea Schmitt are my best chance at hauling in enough organic fish to ship home. Deckhands like Emily Leggitt mean the difference between losing a big fish, or bringing it to the net.

in linguistics from the University of California, Berkeley, but she found her calling on boats,

first on whale watching tours in Juneau before heading to Homer. “To see other girls on the job doing it is inspiring, too,” she said. “In this charter community, it doesn’t feel like a male-dominated thing at all.”(DAVID ZOBY)

FOR 20 YEARS, I’VE booked day trips and overnighters with various charter boat companies in Seward and Homer. I’ve paid the staggering prices to have it all shipped back to the Lower 48. Ten years ago I fished with Capt. David Bayes on his boat The Grand Aleutian. His deckhand at the time was Hastings Franks.

David and Hastings had been fishing together for a few years, and the banter between them was often hilarious. Plus, trolling off of English Bay, we boated a limit of Chinook salmon when most of the other charters were striking out. Hastings was a blur on deck – setting the downriggers, untangling lines, netting fish.

David drove the boat and gave instructions. He darted in once in a while to land a fish, or help a customer get the salmon rod out of the rod holder when the drag screamed and a fish pulsed on the other end.

They were at it for years – David and Hastings – boating impressive hauls of king salmon and halibut. They earned a name for themselves in Homer, and beyond, for working hard for their customers, for fishing with creativity and respect for the fish themselves. (Once I caught a kelp greenling somewhere near Elizabeth Island. There was talk of cutting the fish up and using him for bait. “He’s too pretty to kill,” said Capt. Bayes, and he released the fish.)

Hastings took stunning photos of salmon and rockfish, and customers who looked like they had finally found their home, there on the rolling deck ofThe Grand Aleutian.

But these kinds of captain/deckhand teams don’t last. Think Kobe/Shaq – the late Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O’Neal and their wild NBA stint together with the Los Angeles Lakers. Companies

in the competitive charter industry dissolve, or declare bankruptcy. Captains hang it up. Deckhands come and go. Often, the deckhand is a transient person seeking adventure or a change in life. They drift off to seek other adventures, or study for and pass the test to become a captain. Hastings,

Capt. Bayes informed me, is now in school to become an airplane mechanic. And The Grand Aleutian has been sold, replaced by the state-of-the-art Current Lady. This summer, Shannon Zanone, a young woman from Georgia, was Capt. Bayes’ deckhand. I fished with her and saw that she did everything with precision. Her fileting skills dazzled the clients.

Over the years, Capt. Bayes has trained and hired several female captains and deckhands. He is one of the people responsible for the steady rise of women in Homer’s charter fishing industry. Ann Bayes, David’s mother, operates the booking side of Deep Strike. She agrees that David has been out front in bringing women into the fishing industry.

“He hasn’t hesitated,” Ann said. “He tells the applicant, ‘I can teach you everything you need to know about the fishing, but you have to take care of yourself out there and you have to stay healthy.’”

Ann recalled a young woman who had just graduated from law school who came up and fished for a season on The Grand Aleutian. Captain Bayes trained her and they had a successful season, then the woman resumed her life elsewhere.

In fact, David trained Emily Leggitt when she first entered the trade. And I could see it in her pleasant demeanor, her work ethic, her speed on the deck, and the way she smiled as she set lines, worked the downriggers, removed circle hooks from the maws of halibut, and dropped them – bled and trembling – into the fish box.

With a degree in linguistics from UC Berkeley, Emily worked on a whale watching vessel in Juneau, but was encouraged by her captain there to come to Homer. She looked at the deckhand opportunity as a challenge. She jumped in as a deckhand on Bayes’ The Grand Aleutian, and has been going strong ever since. I mentioned to her that one of the things I liked about fishing with Capt. Bayes is that nothing ever gets under his skin. She laughed.

“Oh, I got under his skin a few times that first year,” Emily said. “You should ask him about that.”

But she’s proud of what she has been able to accomplish in Homer. She said David came up with the “Queens of Kings” moniker, but she’s learned to live with it.

“To see other girls on the job doing it is inspiring, too. In this charter community, it doesn’t feel like a male- dominated thing at all,” said Emily. “We do a great job of this. Just because a lot of this requires brute force and strength, doesn’t mean we can’t get the job done.”

to catch your fish, and eat it too, is an experience many people haven’t had. And it’s contributing to the economy of a small community.” (DAVID ZOBY)

A CAREER IN THE charter boat industry is a terribly difficult position, as you have to deal with customers – many of whom don’t know the equipment or what it is that is expected of them. Most of us, after all, are just walleye and catfish anglers from the Lower 48 who never saw a circle hook or the great reels strung up with heavy braid. We know nothing of tides or what techniques are used to fish these salty waters. There are dozens of species of rockfish, and we have never seen one before. So the deck is stacked against us as we step over the gunnels and enter this foreign world.

When your handle becomes “The Queens of Kings,” people begin to expect certain things. But weather and tides can make it impossible for captains to reach their most productive spots. Trips are scrubbed due to foul weather. Salmon runs fluctuate greatly from year to year. Halibut regulations are new every season, or so it seems. For example, last year there was no charter fishing for halibut on Wednesdays. There is often a lot of pressure on the captains to deliver during the 100-day season.

“I run our Instagram, so I’ve been trying to put pictures of all kinds of fishes – not just big ones, or kings,” Chelsea

said. “We don’t always catch big fish.” On the Irish Mist, Emily delivered a short tutorial before anyone began to fish. She described things in a way that all of us could understand. By pulling on the line she showed us what it should look like when a halibut takes the bait. She said that there were rockfish and other fish – too small for the circle hook – that will nibble and steal your bait. When a halibut hits, she told us, there will be little doubt.

“You don’t need to set the hook; allow the fish to pull on your line and the hook will rotate and set itself – it’s kind of like playing tug-of-war with your dog. You don’t want to just snatch it away from him,” Emily said.

Even so, the deck awash with fish, the building swells, the cries of seabirds of various designs – it’s easy to forget everything you are told when you find yourself two hours out of Homer in an ecosystem of which you only dreamt. Or maybe you feel a little nervous and a little delicate in the diesel fumes.

“I’m usually pretty good with directions – you know, I was a rancher all my life,” said Rick, the retired Nebraskan. Now that his halibut was in the box, all he had to do was kick back and take in the surroundings. “But I have no idea which way is north, south. West? I have no idea.”

Yet you can’t blame Rick for not knowing where he was. There were so many whales spouting that it was hard to pay attention to just one thing. Emily and Chelsea told us they were humpbacks, but I thought they were gray whales because they appeared smaller.

“You’re only seeing a fraction of their bodies when they spout,” said Chelsea. And it was true. Later, one of the whales rolled and we could see the enormous pectoral fins towering above the sea. The humpback breached and everyone scrambled for their cell phones.

“Dave, you’re whale good luck,” Chelsea said, adding they had seen the most whales on the days I fished with them. This was possibly the best compliment I had been paid in years.

ON COMBO TRIPS SUCH as the halibut/ salmon trips I went on with Chelsea and Emily, half of the day is devoted to fishing for halibut, while the other half is spent trolling for salmon. After a full morning of catching halibut, Chelsea moved the boat 45 minutes back towards Homer. Emily set the heavy downriggers up and attached the lead cannonballs, which determine the depth of your lures. The crew of the Irish Mist used flashers (large, angled metal or plastic plates

that mimic a bait ball and wobble in the water) and either a lure or a troll herring trailing about 5 feet behind the flasher. The theory is that the flasher attracts the fish and suggests a school of fleeing candlefish or capelin.

We trolled off the coast of an emerald mountain, where several mountain goats appeared as white specks amid the expanses of lush green. Clients zoomed in on them with their binoculars. Emily explained the gear again, but before she could finish her instructions, the starboard rod began to dance and throb.

“Looks like we already have a fish,” she said. It almost felt staged.

One of the customers lurched towards the rod holder and wrestled it free. Soon there was a fat pink salmon on the deck. It was mid-July and pink salmon leapt in the wake of the boat, or boiled in great numbers on the flat calm waters. Emily tried to begin her speech again, but the portside rod went off, and so it continued. Pink salmon began to come to the nets at an alarming rate.

Chelsea often leapt down from the bridge to help Emily net the salmon. Then, she ran back up the ladder and steered the boat, her face beaming the whole time. It occurred to me that the Irish Mist crew was having a ball.

When my turn came, the line peeled out at a blistering rate. Emily said that it looked like I had a big king salmon. Though the king salmon run is usually associated with mid-June, feeder kings are present year-round in this part of Alaska. Kings are known to swim with pinks, and it’s not unheard of to catch several species of salmon when you’re trolling in the summer. The fish surfaced 100 yards from the boat and thrashed its head. I saw the flasher rip across the surface as the fish made another run. The mere mention of a king salmon ups the ante and gets everyone’s attention.

Kings, or Chinook, are the prized fish of Alaska. You must buy a special “king stamp” to be able to retain one, and you are only allowed two per day, five per season. And just because you book a king salmon trip doesn’t guarantee that anyone onboard will land one. They are rare. I never considered myself to be a lucky person, but once in a great while, things go my way. Perhaps this was one of those days?

I was nervous about losing the fish. I tried not to show it. Chelsea maneuvered the Irish Mist so that we were in an optimal position to land the Chinook. She knew which way the current was pushing the boat and which way the fish would likely run. Emily raised the downriggers and held a long-handled net at the ready. But the fish wasn’t nearly done – kings don’t give up easily.

Chelsea told me to reel, reel, reel. But line was spilling out of the reel again and it made no sense to crank when the fish was running. But here, two hours out of Homer harbor, who was I to question my captain? I did as Chelsea told me to do.

Soon, the salmon was swimming at the boat. I reeled to keep up with him. I saw his thick, purplish back break the surface. I saw the tiny spoon in his jaws. Emily told me to walk backwards, away from the fish. I didn’t want to. I wanted to stay there and watch her dip the net under the salmon, to secure it, but again, who am I to question the Queens of Kings?

Chelsea was down now from the captain’s chair. She talked to Emily and I saw the net swing. And suddenly the big, wild fish – a fish I possibly did not deserve – was on the deck and people were slapping me on the back, congratulating me on my success. These were people

who I had just met a few hours before, and now we were celebrating something: The sunlight off the Alaskan Coast, the many whales we had seen, the chance to be out in this rugged place with these fish? Or maybe we had been brought together by our collective discomfort with the sea and our trust in our captain and our deckhand.

WHEN CHELSEA AND EMILY talked about fishing they couldn’t hide their joy. After a few days with Deep Strike, I had enough fish to bring home and share with friends.

I thought about some people who I wanted to gift a few packages of halibut to when I got back to Wyoming. I’d tell them about being whale good luck, and I’d tell them about the new faces I encountered in the fishing world. I’d tell them about the crew of the Irish Mist. ASJ

Editor’s note: For more information on fishing on the Irish Mist with its all-female crew, go to deepstrikeak.com or call (907) 235-6094. Dave Zoby is a freelance writer out of Casper, Wyoming, and the fly-fishing editor at Strung Magazine. Follow him on Instagram (@davidzoby)