Flight Of The Fledglings

Two hunters fly their plane up from Spokane to hunt caribou in Southwest Alaska.

Dodging just about every bullet that fall conditions can throw at them, the men experience a hunt to remember.

By Jim Johnson

Editor’s note: The author originally wrote this just after his trip, then, 32 years afterward, added details he and his hunting partner agreed not to tell their wives.

Vern Ziegler invites me to join him on a hunting trip to Alaska. It’s early October 1977 and he has just purchased a high-performance bush plane called an M5 Lunar Maule Rocket. Vern is a relatively new pilot and I am sure he wants the ultimate challenge – performing as a bush pilot in Alaska.

I jump at the chance, although I have some hang-ups, which I keep to myself. I’m prone to motion sickness and have a fear of heights. But I’m determined not to let this keep me from joining my good friend on his bold adventure. Vern wants a trophy bull caribou for his lake cabin and I want a bull moose rack for my recreation room.

A HARROWING FLIGHT NORTH

On the morning of our departure, I walk into Vern’s Spokane lumber company and everyone acts as though they’ll never see us again. John Estey, Vern’s bookkeeper, shakes his head in disbelief.

Soon we crank up his single-engine plane and head north towards Anchorage. I try to relax as the little craft reaches cruising altitude, but just outside of Fort St. John, B.C., we encounter a bad storm and begin to ice up. It’s a terrifying situation. We find ourselves flying in a solid gray freezing mist with zero visibility. I can’t help but think about the possibility of colliding with another aircraft in the cloud bank.

Vern radios Fort St. John and tells them we are icing up and asks for a radar fix. The reply is, “Sorry, sir, we don’t have radar, you are on your own; good luck.”

Vern glances at me with a look of disbelief as this has never happened to him before.

It just so happens that an employee at my Spokane wholesale shop is taking flying lessons. I borrowed his textbook and read it from cover to cover as Vern has some health problems and if anything were to happen to him, I want some knowledge on how to fly this thing. We are in a most serious situation, for sure – the ice buildup will soon render the plane too heavy to fly. What we need to do is lose altitude and find some warmer air currents to shed the ice, but we don’t want to crash into a mountain in the process.

Vern asks me to take over the controls and sternly instructs me to use the instruments to keep the wings level.

“Trust the gauge, not your instincts,” he firmly commands. Now we are encased to the point we can’t even see out. I’m at the controls leaning hard to one side because my senses are telling me we are in a steep bank, but I hold fast to the instruments and keep it from going vertical.

Vern is scanning a map looking for any high peaks in the area. I say a little prayer, “Please, God, don’t let us kill ourselves the very first day out.”

True, we won’t be around to face the embarrassment, but still don’t want to confirm to the others our stupidity.

We have no choice but to lose altitude. I rejoice as we break out of the clouds and see the ground. The ice dissipates almost immediately – bullet No. 1 dodged.

Moments later we pass over two bull moose, either of which would look just dandy on my recreation room wall.

But this is still Canada, and with dusk we arrive at Watson Lake, just over the Yukon Territory border from British Columbia.

THROUGH THE STORM

The next morning finds me at the controls flying while Vern sleeps. He gave me strict orders not to try and land the plane while he is sleeping, a stunt I tried on another occasion. Not a good idea, for certain, but that’s another story.

By now I am keenly aware of the sound of the plane’s engine. I can’t keep myself from listening for the slightest irregularity. We are putting a lot of trust in this small plane and its single man-made motor.

Then it is my turn to doze and everything is going along fine until I hear the engine cough and quit. I sit up, eyes bulging, terrified, but Vern just grins at me as he switches tanks. She starts running again.

“You scared the hell out of me,” I shout, “don’t do that!”

He replies, “Sorry.”

That afternoon reveals breathtaking scenery but also some severe turbulence. We can see a cloud formation being whipped across a high mountain plateau and we are tossed, jostled and bounced around big time. It gets so bad the door on Vern’s side pops open, and when he can’t get it closed, I reach over his shoulder and try to hold it shut.

Then the door on my side pops open! My arms feel like they are being jerked out of the sockets as I struggle to hold onto the flopping doors – they’re trying to depart from their hinges.

Then we hit an updraft so intense that Vern virtually turns off the power and he informs me we are flying much faster than the design speed of the aircraft.

“Hold on!” he shouts. “When we top out, hope the wings don’t rip off!”

Then we come to an abrupt stop – ca-wham! We smash our heads on the ceiling, despite having our seatbelts fastened. The good news is, we still have wings and our little plane holds together.

Shortly after we land in Burwash, Yukon, a gravel strip in the middle of nowhere. But they do have gas, which is hand pumped out of 55-gallon drums. Having dodged another bulllet, we regain our composure and head on.

Later that afternoon a snow storm forces us down. We land in the backyard of a little service station, motel and restaurant combination called Tahneta. Tahneta is just a wide spot on the Alaska highway about 100 miles short of Anchorage. We spend the night here.

The next morning we find our plane completely covered with ice and snow. Using windshield scrapers, it takes an hour to get it so it will fly. To navigate to Anchorage, the service station owner suggests we fly down the highway to the second canyon to our left. There we will be able to fly down the canyon under the fog.

“This will take you directly into Anchorage,” he says, and he’s right. A 45-minute flight finds us talking with our friends, Ted and Monne Forsi, formerly from Spokane.

INTO CARIBOU COUNTRY

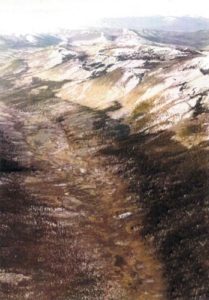

Ted decides to join us on our hunt, and so the next day we are off with Ted in his little red Super Cub followed by Vern and me in the Maule. We fly west out of Anchorage through the famous Merrill Pass and its spectacular scenery – stone walls close enough you feel you can reach out and touch them. There are blue and turquoise ice glaciers, chaparral with the magical profusion of fall colors and rugged majestic snow-capped peaks, but the wreckage of planes lying quiet on the rocks below reminds us of the perils of mountain flying.

I have been frantically taking pictures so as to preserve the experience, but upon completing a 36-exposure roll, wouldn’t you know, I find the camera to be malfunctioning. Probably from all the bashing it took from the storms. It’s a problem I’m sure I’ll fight for the rest of the trip.

We continue to fly west and see several moose including a splendid bull with an antler spread that would go well over 60 inches. Nice, but unfortunately no place to land.

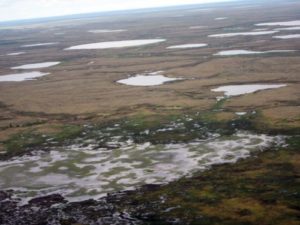

We point the plane south towards the Alaskan Peninsula where we have hunted moose before. The immensity of this unpeopled, snow-clad, windswept land has me spellbound. Late afternoon finds us flying over the flat marshy wetlands of the peninsula. We begin to spot herds of caribou ranging from five to 50 per herd, and including some huge bulls.

It is getting dark when we find a sand dune that appears to be large enough to land on. We buzz the area first, then Ted sets the Cub in. Vern follows and he’s just made his first honest-to-goodness Alaskan bush pilot landing. It is a thrilling and satisfying experience for both of us!

There’s a large bull moose feeding across from us as we set up camp for the night, but Alaskan law states you can’t fly and hunt on the same day, and of course the next day he is gone.

HUNTING FOR BULLS

Before leaving camp, Ted has the presence of mind to erect a pole with a red flag on a nearby knoll. We will be able to spot it from a long distance. We then trek off through the spongy wet tundra in hopes the caribou are still in the area. The marsh land is thick with swans, ducks and geese. Perhaps the greatest pleasure of all are the ptarmigan. They’re turning white for the ensuing winter. I walk into one flock of close to 100 huddled in a sheltered brush pocket.

They seem to cry, “It’s a bear, it’s a bear. Where? Where? Look out! Look out!!”

It’s a foreign but delightful sound to my ears – I would give anything for a tape recorder.

Meanwhile, Ted spots a couple of caribou and then a large herd. Apparently we are still in the midst of the migration, good news We make a stalk on a small group only to find there is nothing worth taking. We encounter another bunch of about 40 which are 700 yards to our right. We glass them and observe a good bull in the bunch. The problem is, they have also spotted us. We try to get within good shooting range but they keep drifting away. It’s almost like antelope hunting. We reluctantly change direction. It is hard to leave that massive male to go after another herd not knowing what it might contain.

We start around one of the hundreds of small lakes that surround us, then decide to sit for a moment and have a quick snack to restore strength. The bulgy tundra is like hiking in a plowed field and we’re expending much energy. As we sit eating, a large band of caribou appear on the other side of the lake just out of shooting range. They also have spotted us. Antlers glistening, they start to run in that beautiful, high-stepping, noble manner characteristic of caribou. Hoping to head them off, we race for a knoll trying to gain the necessary 200 to 300 yards to get within shooting range. There are several good bulls in the group. But they are better equipped and easily out-do us. We catch our breath and watch as they join the herd with the big bull we had given up on.

We’re frustrated, but it is mid-day and with all these caribou together the temptation is just too much. We start back after them, getting to within about 450 yards, but we can get no closer.

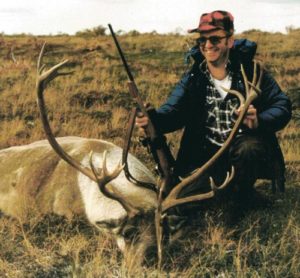

Vern and I have an agreement. On a previous hunt I had shot a large caribou, so he is to have his pick of the caribou and I the moose. While Vern gets a rest for his .300 Weatherby, I watch through field glasses as a stately bull racks his horns in the willow brush. In the meantime, Ted has picked out the bull of his choice.

Vern squeezes off a couple of shots and puts his bull down. I switch and watch Ted harvest his bull.

Then Vern yells, “Jimmy John, give me some help! He’s back on his feet and getting away!” I drop my binoculars and grab my rifle. By now they’re on the run.

“Which one?” I holler as Vern shoots again.

“Fourth from the rear!” he replies.

I pull up one … two … three … and four – sure enough, a bull! I pull out in front and a body width above, then turn her loose. I can hear the splat of the bullet as it hits meat; and watch through the scope as the bull stumbles and goes down facing me. Wow, more than a little proud, what a spectacular shot I just made.

Vern hollers, “Don’t stop shooting, he’s going to get away!”

I realize I’ve made a big mistake. The bull I shot isn’t the same impressive bull Vern has been working on. But before I can regroup, Vern puts his animal away for keeps and we have three caribou on the ground.

What happened, unbeknownst to me, was they split into two groups and I picked the wrong bunch. With it went my chance to shoot a moose – I will be forced to use my moose tag on the caribou. That is legal, but certainly not what I traveled all the way to Alaska to accomplish, disappointing for sure.

WHICH WAY WAS CAMP?

Now wouldn’t you know, it never fails, a storm is brewing as we hurriedly bone and sack the meat. It’s “nerves” time again as we are all aware of the problems we could encounter finding our camp if the gale cuts off our visibility in that flat tract of desolate, monotonous, wet land. The hunt has taken us 2 to 3 miles from our planes and campsite – and remember, there was no GPS in those days.

We struggle with our heavy loads as we start back, but by now the wind is howling so severely we are getting concerned it will upset and wreck our airplanes. We stumble along for about an hour, resting frequently. A migration of 40 to 50 caribou pass close in front of us, including several bulls bigger than the ones Ted and I are carrying.

We’re also watching out for our camp flag, which should be close enough to see by now, but is nowhere in sight. What’s going on, for heaven’s sake? Are we lost? The thought of spending a wet night out here without fire or shelter in this raging storm is frightening, Nothing in this country will burn, and of course, there is a disagreement as to the direction of camp. Vern and I think one way and Ted another. That apprehensive, sick, lost feeling sets deep into the pit of my stomach.

We stagger on, Ted protesting the direction. Vern is out in front and trips and goes face down in about a foot of icy, cold, tundra water. It fills his hip boots and saturates his clothes. The 100-pound load pins him as he labors to regain his feet. Ted and I rush to help him up. Now exposure could come into play. We push on hoping to find camp before dark. Then I think I spot something through my binoculars. Are my eyes playing tricks on me? Have I seen a spot of red?

I stop Vern and Ted. “I may have gotten a glimpse of the plane,” I excitedly state.

We all sit down and stare through our field glasses, seeing nothing but gray. Then, when a gust of wind clears things long enough for us to see it, we spot the red tip of our airplane’s wing sticking out from behind a sand dune knoll a half a mile off to our left. It turns out that the wind has blown down our flag.

With food and shelter within our grasp, we can relax. We arrive to find our planes upright and undamaged by the turbulence, good news as we have dodged another bullet.

Even so, while Vern and I have a lifetime of hunting and packing out meat behind us, with our 40th birthdays behind us, we admit to each other that our days of strenuous big game hunting like this are numbered.

The next morning Vern and Ted fly meat and antlers into King Salmon for shipment back to Anchorage while I tear down camp and place it conspicuously to attract their attention on the return flight. I know there is little danger of them not being able to find me, but with them four long hours overdue, it is a welcome sight when two little planes appear out of the storm clouds – from the opposite direction of what I expected. They eventually admit that they lost me out here in this vast, desolate, tundra. Nice going, guys!

DODGING MORE BULLETS

The hunting is now over and it is time to fly back to Anchorage. A storm is worsening and as we taxi to the end of the sand dune, the added weight of me and camp sinks the tires into the sand and suddenly the strip looks pitifully short. Vern guns the engine waiting for a gust of wind to give us some added lift. It’s nerves time again!

“How much of the dune did I use when I flew the meat out?” he asks. “All of it,” I reply. “That’s what I was afraid of,” he says.

When we feel a gust of wind, Vern pours the juice to her. We come to the end of the gravel and, oh my gosh, we’re not airborne! No turning back now, though. Vern keeps the pedal to the metal, we’re at full throttle, son-of-a-b, we are skipping and splashing through the wet tundra! I have my feet clear up on the dash trying to help her get off the ground. I just know we’re going to flip and crash, but finally we make another bounce and take off.

“Thought we bought the farm that time,” Vern says. “So did I,” I reply.

Another bullet dodged.

Bright and early the next morning in Anchorage we say goodbye to Ted and Monne and head back for Spokane. The few short days we have been gone have changed the landscape we just flew over from fiery autumn colors to a desolate winter vista – colorless, black, gray, white, harsh, rugged, and lonely. It is awesome, but frightening and ghostlike.

Entrusting our lives to that single engine, I again find myself intently listening to her every breath. I am impressed with Vern and his absolute faith in it. The functions and use of the instrument panel are all very familiar now. Visible is the Alaska highway winding through the ice and snow below, a friendly and welcome sight.

But there is a nasty snowstorm brewing up. Vern radios ahead and finds some military helicopters have gotten through, so we push on into the teeth of the storm, all the time losing visibility. As it worsens, we drop down closer and closer to the highway. No turning back, we are committed. It gets so bad we are flying right down above the icy black top. Scary time again! We are on the edge of our seats!

“Don’t lose sight of the highway,” Vern orders, “or we are dead!”

At that exact moment it occurs to both of us: What if a pilot is doing the same thing, except coming from the other direction? As if driving a car, Vern moves over to our side of the road. He has no more than made the maneuver when another plane appears out of the gray blizzard clouds and flashes by on our left.

It’s gone in the blink of an eye. It happens so fast that it is hard to believe. My stomach does flip flops. We narrowly missed a head-on collision. With both planes traveling at 100-plus miles per hour, we would have disintegrated.

After another agonizing 100 miles of snowstorm and seat-of-your-pants flying, we break out of the weather, relieved to have dodged two more bullets!

As darkness approaches, Vern decides to press on for Spokane. It’s another new experience for me, night flying in a single engine aircraft, over a vast uninhabited wilderness with no moon to light our way – it’s as black as inside your hat. Now again, we’re putting all our trust in that little engine. At least in the daylight, with a good glide pattern, we would have half a chance to put her down without killing ourselves. But if she quits at night we’re dead meat.

It’s not my favorite thing to do, so I am more than happy when after hours of pitch black flying, the lights of civilization start to appear.

SAFE AND SOUND

We are now close to home – lights from Wilbur, Davenport and Reardon burn bright through the clear night air, and then we spot the blinking green light that guides us into Spokane’s Geiger Field. We land and I get out and kiss the ground.

Then again, after all we have been through, I feel bullet-proof, like a cat with nine lives.

A month later, as I put on a program for the Spokane County Sportsman Association on our trip, one old pilot gentleman in the audience pipes up and sums it up by saying, “You fledglings had quite a time!”