Book Excerpt: Where The Caribou Roam

The following appears in the September issue of Alaska Sporting Journal:

Alaskan author Seth Kantner’s writing style is much like the remote Arctic wilderness setting he grew up in: rugged but straightforward.

“I try to tell things the way they are, and not take various sides. It’s not easy, and maybe it is strange, but this is how I work to bring people together,” he says. “Maybe this is because I’ve always lived somewhere between the White and Native worlds. And between the human world and the wilderness, too.”

“I’m often disturbed by the fact that groups seem so dead-set on not getting along, especially when I believe this to be vital to our future. Our relationship with caribou is a perfect example – how we view these animals, treat them and how we treat each other concerning this animal tells all there is to tell about us. We can do better.”

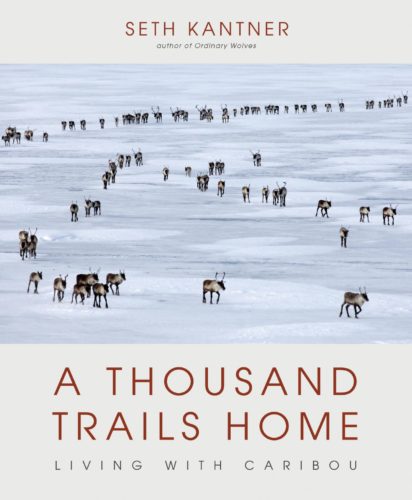

And in previous books such as Ordinary Wolves, Shopping for Porcupine and Swallowed by the Great Land, Kantner paid homage to the natural environment and the wildlife that share the vast stretches of land with him, a partnership that continues today.

His latest project honors the caribou, an animal that to a segment of Last Frontier residents represents a spiritual and physical connection between man and animal. Kanter’s appreciation for the caribou, which he calls an “amazing animal” (see sidebar interview), is deeply personal considering he continues to hunt, photograph and live among the Western Arctic Herd in his Arctic Alaska home. And caribou have a bittersweet history in the 49th state long before Kantner’s time.

The following is excerpted from A Thousand Trails Home: Living with Caribou, by Seth Kantner and published by Mountaineer Books.

BY SETH KANTNER

Yet another sudden shift in reality came to the Arctic in the 1920s in the form of a distant hum from the south. A dot appeared in the sky.

In seconds the hum swelled to a roar and an airship thundered over the sod igloos and tar paper shacks of Kotzebue. Hundreds of huskies howled in unison. Villagers ran outside, staring up in awe and consternation.

The ski-plane circled and touched down, bouncing across snow- drifts, stuttering to a stop. A crowd raced onto the ice and cautiously approached the strange craft. Men peered at the wooden prop and struts, the wings and engine. A schoolteacher and a preacher stepped forward, shook hands with the pilot, and asked for news of the Outside, and where the man had come from; how long was he staying?

By 1927 Ralph and Noel Wien had established a business in Nome serving Deering, Candle, Kotzebue, and Point Hope, and soon small planes became the magic carpets of Alaska, reaching every corner of the territory, connecting far- flung communities by new trails in the sky. Bush pilots’ names and exploits became legendary. Here on the frontier, these men – and a few women – owned the sky and the sea ice, distant mountain ranges, rivers and lakes, and whichever animals they chose to take; they could climb over the clouds, literally soaring over common folks who remained mere specks down below, stuck following old trails on foot, snowshoes, and plodding dogsleds.

Animals were surpassed as the fastest creatures on the tundra. Now, like eagles, humans could traverse unimaginably harsh landscapes in mere hours. A person could climb into an aircraft in Fairbanks, then climb out onto the ice at Kobuk. Before long mail service by dog team was discontinued. Medicine, news, supplies, and even people could now be sledded through the sky! Sick and injured villagers could be transported to hospitals; miners and explorers could be dropped at random points in the wilderness; even food could be hauled north, high above the land.

Not long after airplanes arrived, bush pilots began ferrying north yet another batch of Outsiders. These elite strangers came from around the globe and were willing to pay top dollar to be dropped deep in the wilds, kill a desired animal, and as quickly have a plane pluck them back to civilization, usually with the large antlers, hide, or a once-snarling head of whatever they shot. This new tribe quickly became warmly despised by Natives for competing for animal resources. Before long these Outsiders had acquired the nickname “head hunters” because of the headless animals they left abandoned near their camps.

These days, with so much powerful technology at our fingertips, it’s hard to imagine how worshipped and relied on these aircraft and their pilots were in the wilds of Alaska during the 20th century. And even today, some of these same aircraft – 50-, 60-, and 70-year-old Piper Super Cubs on skis, floats, and tundra tires – remain what they were back in the day: awe-inspiring flying sleds. This Model T Ford of aviation continues to be one of the best airplanes ever built for accessing remote areas of Alaska, and a vehicle of choice for transporting hunters, tourists, hikers, rafters, and photographers far into caribou country.

BY MID-CENTURY, TRANSPORTATION ON the land and water was also evolving. The first outboard motors had come north; slow and heavy, they were infinitely faster than the previous options: paddling, or lining a skiff upstream with dogs and family members pulling ropes while fighting bugs, brush, cutbanks, and current. Evinrude, the first brand of outboard motor, was adopted quickly into Iñupiaq diction, as were the Primus stove, Thermos, and that other wonderful hissing smelly invention, the Coleman lantern.

The chainsaw arrived – louder and smellier still – an incredible luxury item, with its throaty roar ringing out along riverbanks where cabin dwellers cut firewood and house logs. And then, a hundred years after the introduction of rifles came an invention with an equal capacity to alter reality in the north: mechanical snow-travelers.

The arrival in the 1960s of widespread personal motorized transport – snow- travelers (aka snow machines or snowmobiles) and the earlier outboard motors — distorted the time it took to hunt, the distance that hunters were able to travel, and other details of the traditional cultures’ relationship to the land. Unlike aircraft, which remained out of reach for most villagers, snowmobiles were relatively simple and inexpensive, and nearly every local hunter could purchase and pilot one. Previously, rifles had increased hunters’ ability to harvest animals while still retaining much of the focus on the land. Food and furs had remained essential to survival; transportation by sled dogs required more of the same: meat, fish and fat. The new outboard motors, and especially snowmobiles, proved incredible tools for harvesting these needed resources, while at the same time diminishing the need for huge quantities of protein to power dog teams.

Local hunter-gatherer societies, in embracing these machines, soon discovered that the machines had to be fed things that didn’t grow on the tundra: gas, oil and dollars. Also, the snowmobiles and outboards – many built as American recreational vehicles – didn’t hold up under the harsh use by Native hunters in rugged Arctic conditions. Costly repairs requiring more dollars became a fact of life; gas and oil rose steadily in price, and new machines were continuously being manufactured: faster, sleeker, more reliable, and more desirable and expensive.

In the wake of this newest upheaval, hunting pressure increased on wolves, wolverine, lynx, foxes, and other furbearers, a long-trusted source of cash from the wild.

Coincidentally, in the 1970s and early ’80s the prices of furs on national and international markets rose, briefly helping offset the burgeoning local demand for green money. The federal bounty on wolves had been rescinded. Dall sheep were doing well. Moose were moving north with the increase in shrubbery caused by the still-unrecognized change in climate, and along northern watersheds ptarmigan and snowshoe hare and Arctic hare populations hit startling highs, helping support more wolves, wolverine, lynx, and foxes. Marten were rapidly moving north, too, and their pelts, now termed “American sable,” were selling for record amounts.

Voles and shrews experienced a string of successful years – food for furbearers, birds of prey and other animals. Even musk oxen, extirpated in the 1850s by Iñupiaq hunters in northern Alaska, had been reintroduced and were thriving. And the caribou herds continued to grow. Prey was plentiful, furs were plentiful, commercial fishing was expanding, and more and more seasonal jobs were becoming available in the oil industry, construction, forest fire fighting and government agencies. Hunters roamed far and wide on new powerful machines, trapping and chasing down furs – all the while wearing fewer traditional furs and more store-bought clothing and footwear, and eating more store-bought food.

These factors contributed to an uncertain push-pull effect on caribou and other animal populations. Hunters kept wolves and bears in check during the first decades of the snow-traveler era, and with lower demand for dog food, may have aided the recovery of caribou. But at the same time a new phenomenon had been introduced: People could now chase caribou – which can run as fast as 50 miles per hour – and “catch” them. This new hunting practice, while illegal at that time, quickly became accepted, commonplace, and within a generation was viewed as customary.

DURING THIS TIME, ANOTHER technology greatly distorted traditional time and distance on the land. With shaman- like magic, communication had begun beaming voices across the Arctic – news, weather forecasts and even personal messages on Trapline Chatter, Tundra Telegraph and other AM radio bulletins. The Cold War brought more communication, including the Distant Early Warning Line, a series of Air Force radar sites erected along the north and west coasts of Alaska and stretching across northern Canada and Greenland.

This was followed by the State of Alaska constructing satellite telephone and television service in nearly every village, linking isolated communities to the Outside. Locally, households also acquired CB radios for communication between friends, family, nearby villages, and hunters out on snowmobiles and in boats.

On the tundra no one yet imagined the Internet, or the tiny enchanted glass windows we hold in our hands today and stare into, each of us with the power to talk across oceans, see beyond the moon or tap a thought into a stranger’s head on the other side of 100 mountains. But with the massive transformations already taking place, bringing those two welcomed cousins to the north – amazing new forms of transportation and communication – also had to come from their more difficult uncle: the law.

THE FIRST ATTEMPT BY the United States to introduce law and order in the new territory came in 1877 when the revenue cutter Thomas Corwin was sent north to patrol the Bering and Chukchi Seas, assigned to keep piracy, murder, starvation, and such at least microscopically in check. Caribou hunting rules and regulations didn’t yet exist in the area.

It was another quarter century until the influx of prospectors brought the first federal game wardens north. In small communities where life consisted of gathering from the land, folks were confounded by the concept of hunting regulations — as opposed to a person’s abilities, need and luck naturally limiting their harvests. They soon learned to fear game wardens like bad weather or an unexplainable disease, and dealt with the threat in a similar fashion. Lawmen had adopted airplanes for means of transportation, and local hunters learned to watch the sky. When game wardens couldn’t be avoided, hunters used a technique they’d honed over thousands of years; they waited and resumed normal life when the “weather” improved.

In the wake of World War II, with the aid of aircraft, aerial hunting, trapping, and poisoning of wolves contributed to the growth of caribou herds. When the territory became the 49th state in 1959, the federal government still owned most of the land, but enacting and enforcing hunting and fishing regulations across the state became the charge of the new Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) based in Juneau.

With statehood, the industries of commercial fishing continued to grow, as did sportfishing and sport hunting, which ADFG was charged with managing. Subsistence hunting – largely outside the range of harvest reports and subject to shifting external forces – was harder to quantify.

Meanwhile, in northern Alaska, with each passing decade, geologists discovered more minerals – vast deposits of lead, zinc, copper, gold, coal, oil, and gas – under the tundra the caribou lived on. Developers remained stymied by the sheer remoteness of these riches; until, along the northern coast, test wells at Prudhoe Bay

struck oil in quantities rivaling the Middle East reserves: tens of billions of barrels of crude oil. Development of those resources required a megaproject, the 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline, which first required the settlement of aboriginal land claims between Natives, the federal government and the state. In 1971 Congress passed and President Richard Nixon signed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), creating 13 Native Corporations, deeding Natives land and monetary compensation, and paving the way for the Pipeline and other large-scale extractive development.

Out here on the land, the lifting of a pen didn’t instantly alter people’s lives. Alaska was still a frontier. And private ownership of land was not a Native custom. Sudden, invisible changes in land status by distant unknown agencies was ethereal, and old news; it had happened before when Russia had basically “sold the world.” Life had gone on, and did so now. No fences appeared on the vast landscape; folks continued hunting, trapping and traveling, eating caribou, skinning seals, picking berries,

and feeding their families from the land. Biologists employed by the new state continued to study and attempt to quantify the huge and far-flung Arctic herds of caribou. The southern herds – especially the Fortymile and Nelchina herds whose range intersected the road system – were suffering from increased pressure by humans and as a result absorbed much of the money, attention, and management efforts of ADFG personnel. The large northern herds remained distant and something of an afterthought, and attempts to sort them out – as far as distinction between separate herds, range, and population numbers – had consistently proven difficult. This was before modern radio and satellite collars (which came into widespread use in the late 1970s and mid- ’90s, respectively), and before modern photo censuses where individual caribou are manually counted from photographs by human eye (and recently even by computers). Biologists struggled on the ground and in small aircraft to count large numbers of animals spread across a territory the size of the moon, or the Louisiana Purchase, or something equally wild, remote and ridiculously gigantic.

Early censuses were hard to conduct, and not always accurate. Throughout the 1960s the Western Arctic herd had been estimated to be approximately 100,000 to 200,000 animals, and it wasn’t until the 1970s that two large Arctic herds, the Central Arctic herd and the Teshekpuk Lake herd, were definitively identified as separate herds from the Western Arctic herd. Human harvest at the time was an even tougher number to determine and was estimated from the 1950s through the early 1970s to be about 25,000 caribou annually for the entire northwest Arctic, which referred to essentially the entire northern half of Alaska – say 300,000 square miles, an area larger than Texas, with some of the wildest terrain left on earth. While this harvest estimate seemed high, at the same time the herds appeared to be thriving, and in many northern game management units (GMUs) the state did not set a closed season or proclaim a limit, and liberally allowed the taking of cows and calves. Some biologists speculated that the introduction of the snowmobile would lower caribou harvests because of the reduced need for food for dog teams, but that remained to be seen. For now, the hands-off approach by the state showed all the signs of working.

Farther south, rapid changes were taking place in the larger Alaskan towns and cities. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline, one of the biggest projects in human history, was under construction, and for much of the 1970s the state’s politics and budgets – including funding for caribou research and censuses – were dictated by the frenzy of the new oil boom. In urban areas, the human population rose quickly, and with it pressure on nearby game. Both the Fortymile and Nelchina herds suffered population collapses in the 1960s and ’70s, developments that biologists and game managers working for ADFG were strongly criticized for. What happened with those herds would in part affect what happened next with the northern herds: ADFG employees were becoming gun-shy of politics, and the politics of caribou were about to get much worse.

In 1970 the estimate for the Western Arctic herd rose to 242,000. Then in 1976 the census dropped precipitously, with an initial minimum estimate of 64,000 caribou and later revised to 75,000. At the same time, aerial surveys in 1975 and 1976 near northern villages reported alarming quantities of dead caribou – nearly 1,000 wounded, dead and abandoned each year. Biologists believed that the actual numbers were higher than those observed and decided that humans (aka Native hunters) and wolves were responsible for causing this sharp decline in caribou. The crash of the herd in the late 1800s and the half century it had taken to recover weighed on their minds, as did what had taken place with the Nelchina and Fortymile herds. Game managers and the state Board of Game moved quickly to try to remedy the situation and to avoid being blamed for the demise of another large and important herd.

I was 11 when my family and others heard the shocking news: Hunters were to be allowed only one caribou for the entire year! Previously, my dad Howie had shot as many as 80 or 100 each fall to feed us and his dog team, and for paniqtuq and pemmican to last the summer. Caribou were part of the landscape; nearly everyone lived off caribou, more or less. Now across the north, families faced this proclamation from ADFG – which, for people living off the land, was as frightening and ludicrous as if the law had suddenly limited each of us to one blueberry a year.

Coincidentally, that fall, caribou poured through Onion Portage. Villagers also reported another long string of thousands of caribou flowing down the coast past Point Hope, Kivalina and on down to the tent community at Sisualik, passing Kobuk Lake camps and Kotzebue, moving south to Buckland and beyond. For many lifelong residents of northwest Alaska, incongruously, this was the most caribou they had ever witnessed near their communities.

I remember how unsettling and scary it felt when the State of Alaska issued Howie and other hunters a locking metal band to be clipped onto the right hindquarter of their one lone caribou. And how tense that winter was for many families. I remember hunters carrying those silver metal bands, holding them in their big hands, showing them to each other – carefully not clicking them closed and instead saving the band for the next hunt, and the next. How else could one caribou feed a family for a year? Fish and Game issued only 3,000 or so silver bands for the entire north of Alaska and later noted “widespread noncompliance and blatant violation of the regulations.” But from our local viewpoint, we had to eat. And hunting now meant being extra vigilant: Listening for airplanes, working fast, burying gut piles, and kicking snow over blood trails while watching the sky with fear of being arrested.

Rumors and fear swirled through the villages. Was it true that it was illegal to leave a skinny animal? Was it true that it was illegal to feed caribou meat to sled dogs? Did that include scraps? How about guts? Could you get arrested if your dog was gnawing a frozen hoof ? What about a sickly animal? Could a hunter leave it or feed it to his dogs and go shoot a healthy one for his family?

(Incidentally, yes, wildlife managers, in an attempt to further protect the herd, had put forth a proposal to make it unlawful to feed caribou meat to dogs, which inadvertently – or otherwise – severed yet another link to Natives’ former lifestyle.)

Finally, in the summer of 1978, fair weather and that other variable, money, aligned to make an aerial survey of the Western Arctic herd possible. The count came in at 106,000 animals. Good news – except, unfortunately for some people, this increase in just two years seemed too good to be true, almost a biological stretcher, and it was widely believed by residents of the northern part of the state that ADFG had missed a group or groups of animals in the previous census.

(Statistically, caribou don’t have twins, and populations fluctuate depending on quantity and quality of food, cow mortality, calf survival, disease, weather, predation, and other factors. For the Western Arctic population to remain stable, several figures, more or less guidelines, are considered necessary: a calf survival rate [referred to as recruitment] of 15 percent, a parturition [pregnancy] rate of 70 percent, and a survival rate of 85 percent for adult cows. Although herd growth is possible and not uncommon, growth at the rate recorded from 1976 to 1978 is somewhat less likely.)

All good intentions on behalf of the department were buried in the ensuing fray of finger-pointing, as was the fact that the caribou population had been declining, and – regardless of our human hardships – most likely did benefit from reduced hunting. Tight restrictions were eased, albeit slowly, and in the following years hunters were allowed two caribou, and then three, and eventually what we have today: five caribou a day, every day of the year. Basically open season, with virtually no restrictions on hunting practices.

The state’s initial heavy-handed attempts to remedy the situation, however, remained controversial, and have not been forgiven or forgotten. Criticism rained down on ADFG – probably harsher critiques than if the herd had crashed. The department was hammered, and still is, for cultural

insensitivity, racism, endorsing starvation, attempting genocide, and more.

FAR AWAY IN THE bureaucratic world, other government agencies were busy with many more pressing issues that needed to be sorted out – especially if future development was to proceed – and in 1980 Congress passed another act, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), which established varying degrees of protection on more than 100 million acres of federal land. President Jimmy Carter signed the bill before leaving office, doubling the landholdings of the National Park Service (NPS) – 43 million acres of Alaska were suddenly under its jurisdiction – and cementing Carter’s position as this state’s most hated man for decades to come.

The wording of that act, especially ANILCA’s accommodation of rural subsistence priority, was shaped and greatly altered by input and concerns expressed by residents of northern communities – voices arguably a little louder and more insistent in the wake of the caribou controversy. The effects of that act back then were complex, and even today it’s difficult to live with or explain the political, cultural, and environmental quagmire ANILCA created. But in oversimplified terms: across Alaska people believed the federal government was taking what was rightfully theirs – the right to use and treat the land how they saw fit – and feared new laws would limit hunting and fishing, mining and development, and would destroy our various Alaskan lifestyles.

My family was among those people, and very afraid. None of us were absolutely wrong, or right. Probably no one person or group was quite as bad or good, virtuous or evil, as those on opposing sides saw them. But big government was now at the doorstep, and hunting and gathering, living off the land as a way of life, would never be simple again. ASJ

Editor’s note: The book will be available for purchase this month and you can order it at mountaineers.org/books/books/a-thou- sand-trails-home-living-with-caribou. For more on author Seth Kantner’s books, check out his website, sethkantner.com.

Sidebar: Q&A WITH AUTHOR SETH KANTNER

Editor Chris Cocoles chatted with author Seth Kantner, who candidly discussed the inspiration behind his new book, A Thousand Trails Home: Living With Caribou, plus his views on protecting caribou and the future of herds in Alaska.

Chris Cocoles Congratulations on another great book. I know caribou have a special connection to you, your family and your home in Western Alaska, but was there something specific that inspired you to do this project?

Seth Kantner Thank you. This book turned out to be a very long project. Yes, you’re correct; caribou in many ways have been the most important animal in my life, as far as meat and furs, sleeping skins, and the fat they supplied to keep us alive during those cold winters in that old subsistence life.

I’ve been awed by caribou over the years and want to always keep learning more about them, examining what I do and don’t know about caribou, and spending more time near them. This book made me focus even more than hunting and photographing always has on these amazing animals. Also, times are changing fast here and have changed so much already, but caribou remain important to the local culture. For this reason I wanted to delve into and try to understand some of those changed complexities, such as how people hunt, what they do with the meat, what they save and what they leave, how they treat the animals. I think the drastic changes here – and my concern over even larger ones looming – caused me to write this book.

With all the technology we use in our inactions with animals now, we can be frigging dangerous. We have to protect these animals, not just harvest them. I hope people can begin to recognize how fortunate we’ve been to have caribou in our lives – so many thousands of caribou! – and each of us can work to not take them for granted. That’s just the beginning, of course. There are hard choices we have to make if we want to protect what we value.

CC Can you share one of your memorable early experiences with caribou?

SK Migrating bands of caribou (the Western Arctic herd) came through the place where I was born and raised along the Kobuk River in spring and fall by the hundreds, often thousands. My strongest earliest memory is waking up from a nap in the back of our sod igloo – on a caribou hide, of course! I was 2 or 3 or 4 years old,and no one was around and I was scared. I went outside barefoot, the sun hurt my eyes, and the north wind was blowing and cold. I called out, and worked my way down toward the big snowdrift by the river, but no one heard me and no one answered. It was spring – May – and I could see dark lines of caribou crossing the ice coming toward me but that was normal and what I really wanted to see was people, my parents and my older brother. Along the hill near our food cache I finally found them, hunched over a bull caribou my dad had shot. The hair was pale and bleached the way caribou are in spring, with black velvet antlers. The sun was warm there out of the wind and melting- out grass felt nice on my feet, and I was relieved to find my family and know that we would have fresh meat.

CC During your childhood growing up in rural Alaska, what kind of connection to wildlife and the outdoors did you have?

SK That’s a funny question. In some ways connection to the land and animals was all we had! That’s a microscopic exaggeration, but not far off. I grew up out on the land with humans being one of the rarest creatures, and even when people were around most conversations and stories were about wolves and bears and caribou, weather and ice, and hardships – life on the land. Every morning my family looked at the sky, checked the wind and temperature and judged those things against the season and need. What was outdoors decided our day, every day, as far as hunting, fishing and gathering from the land. The other funny thing is we didn’t even realize or really think about our “connection” to the animals and the land.

CC You wrote a lot about your dad Howie in this book. Tell me about the influence he’s had on you.

SK When my brother and I were kids, my dad included us in everything he did, taught us about tracking animals, catching muskrats, plucking geese to save the down, peeling logs, hunting, tanning pelts, rendering fat; all that and so much more. He also did a lot of reading and was interested in old traditional ways, and woodworking, skiing, building kayaks and sleds and boats – always new things and always with us as partners in his ventures. That has continued to this day; his constant desire to learn new things and his open and accepting world view continue to influence me, especially his humorous way of self-reflection and seeing other species as companions in life.

CC I don’t think many in the Lower 48 understand the relationship Alaskans have with fish, wildlife and the natural environment. Can you reflect on that connection?

SK Well, people continually surprise me, and I don’t want to judge folks from the Lower 48, a place I hardly know. I have

This is another reason why I wrote this book – and most things I write – is to try to bring people together and help us see our similarities. In many ways we in northern Alaska greatly value our ability to hunt and fish and our access to huge expanses of wild nature, this without always realizing how incredibly rare and valuable this privilege is in the 21st century. In that way, yes, the connection to nature here is a very strong connection, founded on the past, and at the same time often rough, raw, messy, and resistant to change – even as nearly everything else in our lives has been transformed.

CC After you finished your BA journalism degree in Missoula at the University of Montana, did you always know you’d go back to Alaska?

SK Yes, absolutely. There was never the slightest question! Actually, my longing to be home was so overwhelming I dropped out of college every couple of quarters and returned to the Arctic. Every time I saw a Canada goose or even heard them in the sky I missed home so bad I could hardly stand going to class. I found Montana to be really confining; I didn’t know how to deal with so many fences, and “No Trespassing” and “No Hunting” signs. I felt like I could or would get arrested if I tried to do most of the things we think of as normal life here in Northwest Alaska.

CC You’ve worn a lot of hats in your life: fisherman, trapper, igloo builder. Is there something else you want to accomplish professionally?

SK For a while I’ve been wanting to try being a comedian. I still hope to. I was on my way in that direction when this PC culture flared and all these waves and currents of identity politics started sloshing. Things will have to settle out before I’d attempt that now!

CC The Western Arctic Caribou Herd has seen a large decrease in the last 20 years. How concerned are you going forward with that herd and caribou in Alaska as a whole?

SK I’m very concerned. In my opinion, every one of us should be. Caribou don’t simply just really matter and provide meat; they define us. That’s relatively easy to spot here, but I’d also hope people far away – in Chicago, or Berlin – or wherever, understand these animals define them, too. These last vast roaming herds stand as markers – or barometers maybe – of who we are as humans and how far we progress, or digress. Our ability to get along with each other, understand the importance of nature, look ahead, curb our boundless desires, use our heads judiciously in our power over the natural world – it’s all on the line with the caribou. Caribou are amazingly adapted to the tundra; they are tougher than we can imagine living the lives I describe in this book, but their future will no longer be decided solely by them and the wild.

CC In terms of sport and subsistence hunting, what do you think is working, what’s not working and what needs to be changed?

SK That’s another complicated question, and sadly a political one, too. The complexities go on and on – you might as well ask me about guns or race relations! This is another reason I wrote this book, and definitely another reason it took so long. Here in Northwest Alaska – and across Alaska – the two groups often are at odds, and there are hard feelings on both sides. At the same time few people notice, or are willing to notice, that subsistence hunting is getting more like sport hunting, and vice versa. I mean, the amount of money and resources expended to hunt is expanding, while the time spent doing so is shrinking, and there’s a diminishing understanding of the animals, the animals’ relationship to the land and the use of the various animal parts, too. In ways, sport hunting too is changing; laws now require the harvesting of most of the meat, and many hunters are more interested in taking it home and eating it. What needs to change? For starters, a recognition that we are all in this together. Examining our similarities is not always what we do best, but where we have to start.

CC And in Alaska, protecting the natural resources has been a hot-button issue with the Pebble Mine, and closer to home for you, the proposed Arctic National Wildlife Refuge drilling. What’s your take on these potential projects and what can be changed going forward to ensure future generations can continue the lifestyle you and fellow Alaskans have for so long?

SK This is true. Actually, even closer to home for me is the proposed Ambler Road, or Brooks Range Road, a project that mega-corporations – Outside mining interests – are attempting to push through that would get the government (state and federal) to pay for access to minerals in the Brooks Range. If this road is built it would lead to an expanding spider web of roads throughout the land used by local villagers and by the Western Arctic herd – disastrous for caribou and the way of life we have here. Not good for the planet either. Recognizing that, and not listening to rhetoric and propaganda, is so important to our future.

We are not going to have an amazing wilderness where we’re allowed to hunt freely and have it also be an industrial zone. That’s just not possible. This book is my attempt to try to make people aware of this grave choice that they don’t always even know they are making, here in NW Alaska, in the Arctic Refuge and down by Bristol Bay, too.

CC As for the projects you’ve written such as this new book and others like Ordinary Wolves, Shopping for Porcupine and Swallowed by the Great Land, they all seem like very personal parts of who you are and where you’re from. How sentimental have you been crafting these works?

SK Well, you got me. I am sentimental. I respect the old ways and the old days immensely, and the tough individuals – human and animals – that walked this land. I think as Americans a lot of us feel this way. Our myths about ourselves are made of truths, and those truths tieustowhoweare.Wecan’tletgoof everything, and we shouldn’t. CC