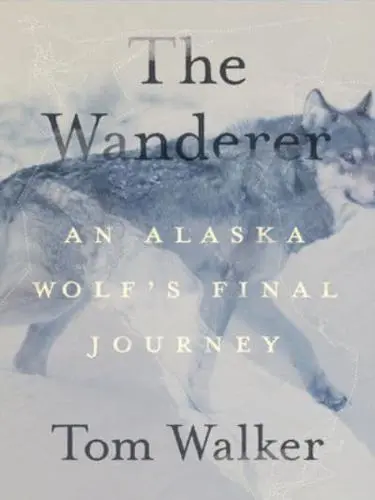

Book Excerpt: Meet ‘The Wanderer’, A Remarkable Wolf’s Alaskan Journey

The following appears in the July issue of Alaska Sporting Journal:

Tom Walker is a Californian by birth, but in six decades of living in remote Alaska – he now resides in a Denali National Park-area log cabin – he’s been humbled knowing what Last Frontier wildlife endure to survive.

“Living in 40- and 50-below-zero (weather conditions) and then in the summertime being assaulted by mosquitoes and every other kind of thing, it’s just a very difficult life out there,” Walker says of what wolves and other critters face in the unforgiving harshness of Alaska. “And predators especially have a really difficult time, as easy as some people think it might be.”

Consider this from Walker: “Eighty percent of all red fox pups born in spring are starved to death by September.”

One wolf in particular piqued Walker’s curiousity enough to want to chronicle its life. Technically known by its assigned number, 258, the animal has been forever labeled the Wanderer for the nomadic journey it went on through the remote wilderness of the Alaskan Interior. Thanks to a GPS collar, its travels were tracked as the remarkable animal defied the odds on a course that took it from near Eagle, Alaska, north to the Arctic Ocean, west to the Dalton Highway, and then south of the Brooks Range.

“One of the most astounding parts of his journey was how successfully he avoided violent or fatal interactions with other wolves,” says Walker, whose book Wild Shots: A Photographer’s Life in Alaska was featured in our October 2019 issue. “Because he was definitely on the move in a lot of country looking for a mate, and yet he was able to persevere as long as he did.”

Walker recently caught up with a trapper friend who’d caught a wolf and was asked if he thought about the possibility that the animal could have possibly covered hundreds of miles to reach that point where it was trapped.

“I would hope (the Wanderer’s journey) would give new appreciation to people regardless of their viewpoint of wolves. How difficult it is for an animal to make a living,” Walker says.

And it all started when this wolf lost its significant other, prompting the walkabout of a lifetime.

The following is excerpted from The Wanderer: An Alaska Wolf’s Final Journey, written by Tom Walker and published by Mountaineer Books.

BY TOM WALKER

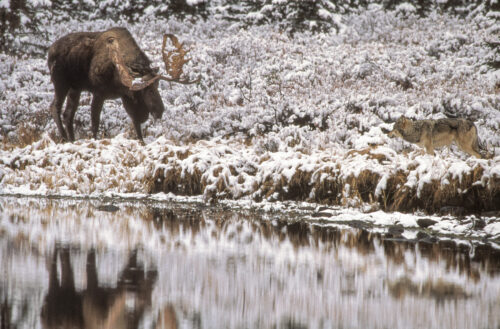

Heavy snow fell in early December, the silt banks, cliffs and forests turning white, the slack waters skimming over. A cold snap descended, prolonged minus-40-degree Fahrenheit temperatures freezing the rivers and lakes. On the Yukon, ice fog drifted above open leads and tortured ice. Near the winter solstice, with daylight less than four hours long, the wolves trotted upstream on the iced-over Yukon River. The cold made travel easier for the wolves and foraging difficult for moose and caribou. The wolves hadn’t fed in days and needed to make a kill.

On Christmas Eve, the wolves killed a moose three-quarters of a mile upstream from the mouth of the Nation River, a prominent tributary of the Yukon, 46 river miles downstream from Eagle. A half-inch of snow fell that day, adding to a 2-foot base. The thermometer read minus-18 degrees Fahrenheit, a slight break from the prolonged cold snap of persistent 40-below temps. The kill site was just outside the two wolves’ territory and on the edge of the Nation River Pack’s territory. Because wolves vigorously defend home ground, even this short incursion into a neighboring territory was perilous, but hunger is a powerful motivator.

Moose are dangerous prey for one or two wolves to attack. A big bull weighs 10 times more than a wolf. A single kick can kill, or break a wolf’s jaw, shoulder or back, resulting in a lingering death. Due to the rigors of the rut, which ends in early October, bull moose enter the winter in relatively poor condition and may be further weakened by deep snow and prolonged cold. The radio collars gave no insight into the wolves’ successful hunt, only that they’d made a kill, confirmed by an aerial fly-over. Wolves more often than not fail to bring down moose they attack. Perhaps this moose had been injured or debilitated.

The two wolves spent the next two weeks near their kill, gorging as much as 22 pounds at a time. The downed moose would last them for days, unless run off by another pack. When prey is scarce, adult wolves can endure for days and even weeks without eating. A wolf can survive on about 21?2 pounds of meat per day, but require about 5 to 7 pounds per day to reproduce successfully. Ravens and gray jays pilfered meat from the moose carcass, their comings and goings betraying the kill to other scavengers.

IN MID-JANUARY, THE wolves left the Nation and trotted back downstream on the Yukon River to the mouth of Washington Creek. Whether they were driven off their kill or had exhausted the meat is unknown. In tall timber near the creek mouth, the wolves made another kill, perhaps a caribou or moose calf, or scavenged carrion, spending three days between a small frozen lake and the Yukon. This was well within Wolf 227’s core territory and she knew just where to find moose browsing in the willows, or caribou cratering for lichens on the higher ridges.

The two wolves’ GPS/collars revealed their day-to-day movements and how they crisscrossed their territory in search of food. The bitter cold and darkness daily tested their hunting skills, strength and resiliency. In withering wind and cold, the two wolves again returned to the moose carcass on the Nation.

On February 6, Wolf 227 weakened and died in an alder thicket on a steep hillside above the old kill. Breeding season for wolves was just days away, but now Wolf 258 was alone.

Wolf 227 could have died from any number of reasons – accident, disease, injury, or conflict with another pack. By the time biologist John Burch visited the site to retrieve her satellite collar, a wolverine had scavenged her remains, obliterating any chance to determine cause of death. Judging by her recent movements, coupled with lack of recent hunting success, Burch believed that she’d grown desperate and starved.

One of Burch’s colleagues takes an alternate view and doesn’t believe Wolf 227 starved because she was in “excellent” condition just three months earlier when recollared, and had been making kills in her territory prior to killing the moose on the Nation River. Because the moose kill site was inside the Nation Pack’s territory, he believes other wolves killed her or she was mortally injured during an attack on another moose. Whatever the cause, immediately after her death, Wolf 258 abandoned the site and cut back to familiar ground in the highlands above Washington Creek. Twice in late February, he returned to the Nation River, spending the better part of three days apparently searching for his companion and risking possible contact with the Nation Pack.

Wolf 258 had spent the next two months coursing the very heart of Yukon- Charley Rivers National Preserve, from the river’s edge to the highest summits .

He endured extreme cold, slicing winds, and long bouts without food. He’d lost his partner, but alone, had survived. His next move would ultimately determine the course of his life.

EARLY ON THE LAST day of April, Wolf 258 plunged into the ice-choked river and fought for the far bluff, dodging nearly a half mile of grinding ice and bergs the size of small cars. Fighting the powerful spring flow and slamming ice, he used the eddy at the end of a small island for respite before forging on. Somehow uninjured, he reached the far shore and dragged himself up the shelf ice to the base of the rocky bluff towering over the river. Later that morning, in sharp sunlight, Wolf 258 stood atop Biederman Bluff looking down at the broad bend of the Yukon. It would be the last time he would see the river. ASJ

Editor’snote:OrderTheWanderer:AnAlaska Wolf’s Final Journey at mountaineers.org/ books/wanderer. It’s also available on Amazon and other online retail outlets. For more on the author, go to tomwalkerphotography.com.

TALKIN’ WOLVES AND MORE WITH AUTHOR TOM WALKER

Alaska Sporting Journal editor Chris Cocoles caught up with Tom Walker, author of The Wanderer: An Alaska Wolf’s Final Journey, who discussed all things Canis lupus – plus a few other topics – with us. (This interview has been edited for clarity.)

Chris Cocoles You’ve had a lot of wolf experiences in your life. Did this particular story fascinate you enough to pursue this project for a book?

Tom Walker A couple of things. I’ve lived in Alaska for over 60 years and worked a short while for the [U.S.] Fish and Wildlife Service and a short while for [Alaska Department of] Fish and Game, and I had a lot of opportunities to have observations and some close contact with wolves. And people over the years have asked me, “When are you going to tell the stories and write a wolf book?” And I never wanted to write one for the simple reason that there are these polar opposite views of wolves that turn to advocacy one way or another. But they’re fascinating animals. By no means am I a wolf hugger; by no means am I a wolf biologist or anything like that. In fact, they’re not even my most favorite animal. But I like all wildlife and I wanted to tell a story. If I was going to talk about any animal, it was because of fascinating behavior. And when I first heard about this animal 10 years ago and the distance it traveled, now there’s a story. If that can be done right, there’s the story of how animals live. How they deal with this life that is so hard and so harsh. When I saw that story, I said that’s the story I’ve got to tell.

CC Was this wolf “the Wanderer” a unique example of the way it traveled? TW Yes; it was a very unique situation. The fact that was elucidated by David Mech, the famous wolf biologist, is that wolves die one of two ways: They starve to death or they’re killed by other wolves. The fact that this animal could go all of those miles and through maybe hundreds of other wolves’ territories and avoid being killed by other wolves and last as long as he did and survive, is just a remarkable story.

CC And while wolves do travel a lot as their behavior dictates, did the Wanderer literally wander for longer and more of a distance than maybe any other wolf ever has?

TW Well, you can say that if you put in the caveat of “that we know of.” The only reason why we were able to parse out this story and others of traveling great distances is because of radio and GPS collars. He’s likely not the only wolf that’s ever gone that far and not the only wolf that has survived like that and ended up like that. But that’s the only one we know of for sure.

GPS collar data has helped flesh out the long-distance dispersals of wolves, some of which are known to have travelled thousands of miles. “The fact that this animal could go all of those miles and through maybe hundreds of other wolves’ territories and avoid being killed by other wolves and last as long as he did and sur- vive, is just a remarkable story,” Walker says. (TOM WALKER)

CC Are wolves kind of complicated in terms of figuring out their behavior patterns?

TW Not necessarily; I wouldn’t say that. All of us involved in this are being confounded all the time by new discoveries because of the science involved in all of that. But a lot has been known about them and it’s being refined. And some of the things that we are discovering are the interrelations between populations that are more widely scattered than we ever thought before. Recently, we found that the Denali National Park wolf population is more closely connected to the population in Yukon-Charley [Rivers National Preserve], which is many hundreds of miles away, than any other group in Alaska. So there are discoveries genetically, behaviorally that we’re finding out that we didn’t know before.

CC When the Wanderer’s mate Wolf 227 passed away, did that death have a big effect on how his journey unfolded? TW I would say definitely. Again, I’m not a scientist, but he did abandon an established territory that had been his and hers, and that she had controlled and had been all of her life. And then after she was gone he hung around there for a couple of months and then took off. And if she would have lived they would have bred. She died just a month or so before the breeding season. They would have likely started their own pack there in that central part of the Yukon-Charley. But after her death, off he went.

CC Was he a heartbroken wolf looking for a new mate/life?

TW Personally, I would never use the word heartbroken, but when that animal took off he was only like 2 1?2 years old, and that’s the time when a large number of wolves leave their natal territory and their natal pack and go off in search of their own territories and own mates. So logically, he’s lost a partner; he’s going to be under the biological imperatives to find another mate.

CC Based on the analysis after his journey, did he reproduce with a new mate?

TW No. He would have had to be paired up and claim territory. He did not have relations with a female wolf enroute or while wandering around. There was speculation that in mid- to late summer of the following year, when he was on the North Slope, that he may have paired up because he localized to a specific area. But that’s not the breeding season.

CC Do you have lots of admiration for this wolf?

TW Oh, you’d have to. I’ll just give you one example. He crossed both the Yukon River and the Porcupine River at breakup. A couple weeks ago I was up on the Yukon to watch the breakup, and when you see the power of that river at breakup – and there was a lot of flooding damage to some communities – of these huge ice blocks the size of cars being thrown up on the bank and slamming together, to think that a wolf swam or somehow crossed both of those rivers at breakup, you’d have to be respectful. When caribou cross sometimes at breakup, the Native villagers on the Porcupine have seen them in the water being beaten by the ice flows. You have to have a certain respect for animals that can do something like that.

CC What were some of your personal interactions with wolves?

TW Just as an observer and a few years ago, I spent a few summers in a row with maritime wolves out on the coast to see how they make a living there. They’re a little different from Interior wolves. The coastal wolves feed on salmon and marine mammals and marine life. And it’s fascinating to watch and see how they make a living when they’re not hunting large animals. One researcher said that 80 percent of their diet for a significant part of the year is all marine life.

CC Something that resonated with me was after the Wanderer’s death he was examined and his body was so beaten up. Did it for you too?

TW Oh god, yes. He went from 100-something pounds to 60 pounds. There was another wolf in that same general area, a female that died a few years earlier, and it only weighed 40 pounds. So it’s hungry country.

CC I was also intrigued by when you mentioned how a wolf can sometimes die attempting to kill a larger moose.

TW They’re huge; 10 times as big as a wolf. It’s like that old quote from [author Rudyard] Kipling: “The power of the wolf is the pack.” The reality is a pack of wolves can attack something big and be successful. But a lone wolf? Not so much. … The other thing that was interesting was oftentimes the Wanderer would find himself in wolf paradise. When he was in Ivvavik National Park in [Canada’s Yukon Territory], he was right there at the peak of [moose] calving. And those young calves are just smorgasbords for wolves. They can’t outrun them and they can’t avoid them. The cows don’t defend them from wolves. And yet he didn’t stay. And I guess what you can surmise is he left there because of competition from other wolves … He left behind the best hunting he probably could have had in the whole time he was on the move.

CC I know it’s impossible for us to think like a wolf. But doesn’t it have to be hard to walk away from that abundant food source despite the competition?

TW What I tried to do is not get into his brain and try to think like a wolf. That’s impossible. I looked at the circumstances and tried to come up with a likely scenario.

CC Wolves are such a polarizing animal. Can you put into words just how complicated the species has become?

TW There’s a trapper in our area who’s very outspoken about trapping and going after wolves. And I’ve heard him say more than once countering the opposition that he doesn’t hate wolves. He loves them. He thinks they’re amazing animals that are a challenge for him to trap and hunt and whatnot. And he has an appreciation coming from a consumer’s point of view – or a harvester’s point of view. Whereas people who can’t see his point of view don’t come from that angle. And I tried really hard to stay out of that debate. I only gave the background of why a wolf might be at risk and needing to move to a new area.

CC Are wolves misunderstood?

TW By a certain set of people, yeah. And by another set of people they’re lionized beyond what they actually are. The extremes will never meet in the middle.

CC You mentioned that wolves aren’t your favorite species. What animal gets that honor?

TW People laugh at me when I say this, but it’s snowshoe hares. And the reason for that is you can not name another animal that impacts its habitat and all its neighbors as much as snowshoe hares. They go from almost nonexistent to unbelievably abundant and they can completely destroy their habitat and the habitat of moose when they’re at peak numbers. And when they’re at peak numbers, there are more wolves, more lynx, more foxes, more great horned owls; everything flourishes because of hares. Even grizzly bears catch them and eat them. But when they’re not around, everything crashes. Right now we have a very low number of hares here after a peak about 10 or 11 years ago. There aren’t any lynx and there aren’t many wolves. Everything responds to them and they have the power to change their habitat.

And the other thing that’s pretty astonishing is a female can have almost 30 young a year and five different litters. They can conceive the same day that they give birth. They can have their young in the morning and later in the day can conceive again. It’s a pretty amazing animal. I can sit right in my living room in late winter and watch their spring breeding activities. And they’re fascinating to watch.

CC What’s one of your favorite memories of living in the Last Frontier?

TW I’d been in Alaska three years, and when I grew up, out of college I worked as a packer taking hunters and fishermen out in the high eastern Sierra [Nevada Mountains] of California. My dad was a very avid fisherman and he had only really caught really tiny rainbow trout. So I had him come up one year salmon fishing and we went out and caught salmon. I’ll never forget how excited he was, and he was nearing the end of his life, to be catching fish like that. The first one he got on his line and pulled it in, his eyes were as big as Noah’s must have been when he built the ark and had all the animals on there. But he was so thrilled; so thrilled. That is the best highlight of my time in Alaska.

CC Has Alaska been everything you hoped it would be after all of these years?

TW Yes. But what’s been hard to appreciate are changes – the modern era of all the industrial tourism; that’s been a hard thing to watch. It’s changed so much in Alaska – not for the better. But all in all, I’ve been extremely fortunate and very lucky to have come here.

CC How much has climate change made it even harder on Alaska’s wildlife?

TW For everything – moose, sheep, caribou, wolves. It’s like the mosquito season is longer and more intense. The vegetation is changing dramatically. So there are going to be winners and losers in all of this. Some species like caribou and sheep are going to suffer more than, say, moose, which are expanding their range. So it’s affecting everything in very subtle ways and in some not so subtle.

CC To that point, long after we’re both going to be gone, are you concerned about the future of Alaska ecosystems?

TW For the whole world. It’s changing and the climate change thing, you’d have to be blind and stupid to not see it everywhere. ASJ