Best Stories Of 2022: Here’s To Great Content For 2023!

Happy New Year! As we say goodbye to 2022 – let’s face it: It could have been so much worse! – here are some of our favorite print pieces from the year and look forward to us all having a happy 2023.

JANUARY: Cashing in on a Kodiak goat hunt.

With any hunt, the odds are stacked against you. As famed archer Jack Frost says, hunting with a bow starts where hunting with a rifle ends. And closing that last 200 to 300 yards to get in bow range drops your odds considerably. We watched on the third day as Trevor snuck into his intercept point once two billies left their feeding area to bed for the day.

He made his play as the goats walked back to their high point. As Trevor went into position with a goal of intercepting the billies at their evening feeding grounds, I went to hunt a different area.

Eight long hours later, I was across the valley watching as the goats fed directly to Trevor. It was like watching a live TV hunting show as the two billies fed directly at him.

As they closed the distance, I felt the hair stand up on the side of my neck due to a shift in wind. As the goats got to 100 yards, that wind also betrayed Trevor’s position and he was caught. The billies fled the area and headed right back to their bedding ground. If he had been hunting with a rifle, it would’ve been a sure thing. But with a bow, the odds are against you tenfold. …

Luck was on our side. It was a partly cloudy day and the fog was dropping and lifting into the valley consistently. As the fog dropped, we moved. We were able to get on the ridge using this technique and get out of sight of the two billies.

The wind was in our favor as well, blowing from the two goats back to us. We took our time and used the mountain to hide our movement.

As we closed in, we ranged one of the billies at 95 yards. He was behind a small rock, but it allowed us to get all the way down to 18 yards. Trevor made a perfect shot and was successful in taking another goat. -Brian Watkins

FEBRUARY: A Husband And Wife Team Up For Adventures

WE’VE BEEN MARRIED NEARLY 32 years and our lives have never slowed down. After teaching in small schools for seven years in the Arctic, we moved to Sumatra, Indonesia, where we taught at an international school for four years. We started our own family and eventually moved back home to Walterville, Oregon east of Eugene.

In 1997 I started dabbling in outdoor writing. My first book, Hunting The Alaskan High Arctic, became an all-time best seller for the publisher. By 2001 I felt I could make a living in the outdoor industry as a full-time writer. I made $11,000 that year. But I was forming valuable relationships and soon speaking opportunities and TV hosting jobs came along. The timing was right.

Before I knew it, I was traveling the world hunting and fishing and hosting multiple TV shows. My writing career also boomed. Some years I was in the field over 280 days. Then, when hunting season was over, the speaking circuit began, and that’s where Tiffany came in.

Though Tiff and our two sons joined me on many hunting and fishing trips and were part of the TV shows, it was Tiffany’s ability as a wild game cook that paved her way into the industry. During our time in Alaska we ate only the meat we caught and killed. We ate fish and game every single day. We did – and have always done – our own butchering. With Tiff’s cooking abilities and vast diversity, she was quickly in high demand by companies in the outdoor industry.

Soon we were speaking three months of the year at big events like the NRA Convention and many sport shows around the country. One weekend we’d be in Charlotte, another in Sacramento or Portland, Las Vegas or Nashville, and more. I offered seminars on hunting and fishing techniques, while Tiff gave many on wild game cooking.

But our favorite seminars were when we worked together. Oftentimes whole deer or pigs were brought; we butchered the entire animal, and then Tiff would work her magic, whipping up some great recipes to feed the attendees. To this day she’s the best cook I’ve ever met. We still eat wild game and fish every day. I don’t like going to restaurants because they’re never as good as what Tiffany cooks up -Scott and Tiffany Haugen

MARCH: Meet Homer’s Queens of Kings

Over the years, Capt. Bayes has trained and hired several female captains and deckhands. He is one of the people responsible for the steady rise of women in Homer’s charter fishing industry. Ann Bayes, David’s mother, operates the booking side of Deep Strike. She agrees that David has been out front in bringing women into the fishing industry.

“He hasn’t hesitated,” Ann said. “He tells the applicant, ‘I can teach you everything you need to know about the fishing, but you have to take care of yourself out there and you have to stay healthy.’”

Ann recalled a young woman who had just graduated from law school who came up and fished for a season on The Grand Aleutian. Captain Bayes trained her and they had a successful season, then the woman resumed her life elsewhere.

In fact, David trained Emily Leggitt when she first entered the trade. And I could see it in her pleasant demeanor, her work ethic, her speed on the deck, and the way she smiled as she set lines, worked the downriggers, removed circle hooks from the maws of halibut, and dropped them – bled and trembling – into the fish box.

With a degree in linguistics from UC Berkeley, Emily worked on a whale watching vessel in Juneau, but was encouraged by her captain there to come to Homer. She looked at the deckhand opportunity as a challenge. She jumped in as a deckhand on Bayes’ The Grand Aleutian, and has been going strong ever since. I mentioned to her that one of the things I liked about fishing with Capt. Bayes is that nothing ever gets under his skin. She laughed.

“Oh, I got under his skin a few times that first year,” Emily said. “You should ask him about that.”

But she’s proud of what she has been able to accomplish in Homer. She said David came up with the “Queens of Kings” moniker, but she’s learned to live with it. -Dave Zoby

APRIL: Coho bite challenging on Juneau trip

We managed to get a couple fish on our usual assortment of Arctic Spinners, which Chad had never seen before. After chatting about the bite we just witnessed and mentioning our lack of foresight to actually pack the right lure, Chad was kind enough to give us a couple Flying C’s. No money, no tense negotiations. Just here ya go and good luck, fellas.

I scrounged up a few of the pink Arctic Spinners that we were starting to get bit on and handed those to Chad in return. At the end of the day, we all just want to get bit and a random act of kindness got us over the hump.

And the silvers finally got over their case of the stupids and started acting like Alaskan coho, as in inhaling our presentations. We nicknamed our Flying C’s “The Chad” and were happy to announce it when a fish was hooked on our new friend’s lures. Full ropes and quickly filled fish boxes became the norm as coho numbers built with each incoming tide.

The best part about a good bite is everyone around tends to be in a good mood. Shouts of “Fish on!” and wide grins and celebratory cigars became common the next couple days. It was a welcome change from sore shoulders and the angst of an all-day grind. -Brian Kelly

MAY: Living with bears is quintessential Alaska

One September when I was in King Salmon, the proprietor of the Antlers Inn warned me to not walk the nearby street at night. Bears, she said, use it every night coming to and from the river. I ran into a number of parties from around the world that had traveled to the small Bristol Bay community to see and photograph bears.

Just a short floatplane flight from King Salmon is Brooks Camp and the famed Brooks Falls, the most visited bear- viewing area in Alaska. Brooks Camp is managed by a team of park rangers who make sure bears and people coexist as peacefully and respectfully as possible. It is incredibly rare, despite bears and people often being in close proximity, for contact between bear and person to be made at Brooks Camp. One of the key factors for Brooks Camp’s success avoiding negative interactions between bears and people is that human food and garbage is kept on lockdown.

Brooks Falls also acts as the setting for the internationally celebrated Fat Bear Week (Alaska Sporting Journal, November 2020), where people get to tune in virtually to Brooks Falls, judge which individual bear is the “portly patriarch of paunch” or “king of the capacious creatures of Katmai” – i.e. fattest – and cast their vote online. The competition has become increasingly popular and provides a way to educate people on the natural history of Katmai bears, the value of salmon and the interconnectedness of the ecosystem. -Bjorn Dihle

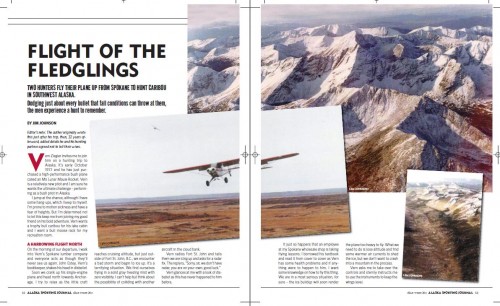

JUNE: A caribou hunt to remember

Nick gave me a piece of advice that I will carry with me in the future. He said when the caribou are migrating, let the lead cow and a couple more pass, then sneak in.

We had spotted a small group of caribou in the bottom of a valley, so I made my way toward them. They were migrating and moving fast. I had to speed hike down ahead of them. As I got to where they were, they pulled their vanishing trick. I glassed for the herd and found nothing. I was about 2 miles from where Trevor and Nick waited for me.

With my head hung low in disappointment, I caught movement ahead of me. I saw a cow and a calf jogging in my direction. Recalling Nick’s advice, I sat low in the waist-high snow to keep out of sight. The cow and calf sped past me and I started to run to their trail knowing there could be more behind them.

As I closed in on the position I wanted to be in, a small bull spotted me and changed course. Before, I would’ve tried to move again and get in front of him. But thanks to Nick’s tip, I went to where the cow and the calf had set a path.

It wasn’t easy to get to that spot. I ran through a small boulder field that was covered in snow, slipping, sliding and flailing all over the place. It would’ve been rather entertaining to watch.

I sneaked into 40 yards of the path in the snow and waited. The herd that I had lost was on their way down the trail. A big bull with sweeping back tops came along and I let an arrow sail into his lungs. He ran 50 yards and piled up!

When I got back to Trevor and Nick, I faked being sad and kept my smile hidden with my head low. They read right through it after they saw my quiver was missing an arrow. We had killed two awesome bulls. -Brian Watkins

AUGUST: Inside Kenai’s “World’s Most Responsible Fishing Tournament”

The proceeds from the tickets sold in all the tournaments – Ostrander said last year’s event sold an all-time high 194, and has been steadily increasing during most of its short run – plus additional sponsorship donations will eventually be used for a Kenai River restoration project that is being mulled.

“The whole concept behind it is not only conservation of the resource being the fish, but also protecting and conserving the river. We’ve been accumulating the revenues from the derby over the previous five years, and we have the anticipation of trying to conduct a significant project that would benefit the river. And this year we started looking at possible projects,” Ostrander says.

“We haven’t pulled the trigger on any of them yet, but we want to make sure the project is highly visible to the public and makes a meaningful, positive impact to the river. So we’re being selective.” One possible idea Ostrander and his colleagues have discussed focuses on restoration work on several small Kenai River tributaries located in and around the community. The plan would partner the derby and Kenai Chamber of Commerce with the Kenai Watershed Forum and other agencies.

Ostrander says it’s surprising how important “these small little trickles are, particularly to coho stocks.”

“They’re not for spawning, but for the rearing of the smolts that are just all over in these little streams,” he says. “So protecting those and increasing the quality of the habitat along those streams is all really critically important to preserving coho stocks.” -Chris Cocoles

SEPTEMBER: Klawock Groups Work Hard To Bring Sockeye Home

When he was younger, Carle remembers dipnetting for salmon right off the beach. For a month straight, he said, Klawock would smell of salmon as they spawned, washed downriver and washed up on the beach. “The fish were going through so much” in the creeks, he recalled, “you were able to come here and just snag them, or grab them with your hands.”

Back in 1868, the first salmon saltery and cannery in Alaska was built in Klawock Inlet. In the early 1900s, cannery records show a commercial harvest of 80,000 sockeye.

Last year, about 3,400 sockeye salmon made it up the river, Aboudara said.

Even in his lifetime, the Klawock Lake sockeye return has experienced a significant decline. “I remember being able to fish and in a single week we would have enough fish for my family, my community members, my friends, extended family,” Aboudara noted. “Nowadays you could go all season and not even have enough fish for your household.”

The community worked together with scientists from Juneau to make a plan to help the fish. This project is one piece of the Klawock Lake Sockeye Salmon Action Plan (alaskawatershedcoalition .org/2020/02/klawock-lake-sockeye- salmon-action-plan), authored by the Southeast Alaska Watershed Coalition, the Nature Conservancy and Kai Environmental Consulting Services, in consultation with tribal, Native corporation, government, nonprofit and private sector partners.

“The Indigenous people of Klawock are sockeye salmon people. And to have these kinds of declines, to have this kind of impact in my own lifetime, let alone the generation before, it’s detrimental. It hurts our spirit,” Aboudara said. “We’re doing our (best) out here to help at least give the sockeye a bit more of a fighting chance so that future generations will know what it’s like to have these fish.” -Mary Catharine Martin

SEPTEMBER: Southeast Alaskans Talk Climate Change Effects

NWF Outdoors hosted a community forum in Juneau, with sportsmen and -women and those who rely on the natural resources weighing in on issues in their backyard.

When they were out seeking coho, the talk was that the fish were late arrivals during the usual August run. Kindle is quick to point out that he can’t necessarily blame salmon tardiness on climate change.

“I can’t do that, but it is indicative of things changing and that just kind of follows the form of what we’re hearing up there. No matter where we go or who we talk to, it’s that things are off,” he says. “The timing of migration and when things show up. When plants start budding or when fall comes and the snow comes. All of those different timing things are something we hear every time we go (out in the field).”

The sprawling Tongass was also on the minds of the locals. As its old growth is threatened and the Roadless Rule has been under assault to potentially allow large-scale logging, America’s most massive national forest is a hot-button topic in these parts.

Kindle got just a small taste of the Tongass, but he called it a “really unique place.” And who could blame any first-time visitor for being in awe of its changing landscape, from the sea up the steep cliffs of the high country? It’s the Alaska that Lower 48ers see in their dreams, Kindle included.

“It’s one of the biggest and most productive national forests, and the biggest in the United States. And obviously logging has been part of its history. I think like any of these natural resources decisions, a lot of what people want is certainties,” he says. “They want to know what’s going to happen and they don’t like to flip-flop around. ‘We have to protect this, this year and next year with administrative changes.’” -Chris Cocoles

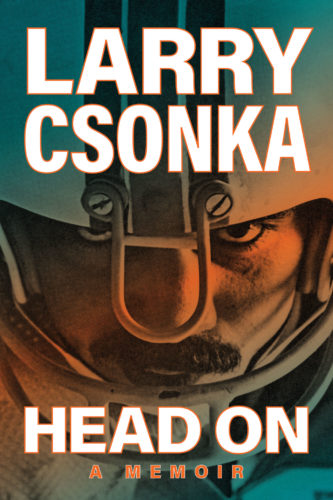

OCTOBER: Football Great Larry Csonka’s Alaska Love Affair

As a kid, I loved fishing so much it inspired my granddad Heath to quote Mark Twain to me.

“You know,” Granddad would tell me, paraphrasing his favorite writer, “the secret to success is making your vocation your vacation.”

My first hunch about how to do that came in the 1970s during a guest appearance on (sportscaster) Curt Gowdy’s The American Sportsman – an outdoors TV show featuring Curt and celebrity guests who fished and hunted and, sometimes, tackled things like whitewater rafting, hang-gliding, or mountain climbing. After we finished filming a fishing episode, I told Curt how much I enjoyed doing the show – and how I’d always dreamed of living in Alaska.

“You should consider doing this,” he said …

During the first week of September 2005, we traveled to Russian-named Nikolski, the site of a 4,000-year- old village on Umnak Island in the Aleutians, to fish for silver salmon and hunt caribou. The journey to get there was a feat on its own. Umnak lies 900 air miles southwest of Anchorage. We flew commercial to Dutch Harbor, then traveled the last 100 miles in an old PBY amphibious plane.

We always faced some level of risk on our expeditions. That comes with the outdoors adventure territory. But being so far from civilization proved to be more dangerous than we’d anticipated. -Larry Csonka

DECEMBER: A Teenager Follows Family Hunting Tradition

Before coming on this hunt, my dad had taught me the importance of trying to shoot a billy over a nanny. While killing either is legal, not shooting a nanny can help the goat population considerably in the long run. Nannies start mating when they are 4 to 5 years old; they tend to only give birth to one kid at a time. This can make the mountain goat population vulnerable, which is why I believe it is important to try and shoot a billy.

I shoved the gun at my dad to confirm that I was correct. He examined the goat before handing the gun back over.

“Yep, it’s a billy. It’s your shot,” he whispered.

I took a deep breath and settled the gun on my pack. I lined the scope up, my finger shaking on the trigger. My dad whispered encouraging words as I took another quick breath. The goat started walking and I followed it with my gun, pressing the stock of the rifle against my shoulder. The goat turned again and gazed back, the wind blowing steadily in our faces and not giving away our scent.

With one last movement, I found the shoulder and squeezed the trigger. The goat jumped up in the air, stumbling a few feet before disappearing behind the edge of the ridge. I looked over at my dad, then we gathered our packs and prepared for the upcoming search for the goat.

We scrambled over a boulder field to where the goat disappeared and peered down the hillside. The goat was crumpled on the steep slope – only yards from an intimidating cliff. “Congratulations,” my dad smiled, then gave me a high five. “You just got your first goat.” -Braith Dihle

DECEMBER: Bristol Bay Native Trout Quest Comes Down To Last Casts

As the day went on, a new wall of clouds erupted on the western horizon, and our pilot signaled that whenever that plume arrived, it would be time to go.

I decided to fish through lunch.

“They’re out there. We’ll find one,” Chaney calmly told me. Either naturally, or thanks to his academy training, he could tell his client was struggling to hold it together.

Minutes before our pilot warned us we would have to leave to beat the approaching front, the line on my 6-weight pulled taut behind a salmon bed and a heavy tug raced for the river bottom.

I won’t bore you with too many exotic adjectives describing the fight and landing of the fish. All things considered, it isn’t important.

After releasing the beautiful hen char, I sank to my knees in the river and reflected on the nearly 30,000 miles of travel, dozens of beautiful rivers, hundreds of local river stewards and conservationists I had met along the way, and the hundreds of native trout and char that, to me, are the essence of the West. -Daniel Ritz