A Teen Hunter Seeks Ghosts In The Fog

Merry Christmas, everyone! Here’s a great family hunting story that we hope you enjoy on this holiday. The following appears in the December issue of Alaska Sporting Journal:

BY BRAITH DIHLE

Growing up in Alaska, my family has always been involved with the great outdoors.

My grandfather taught my dad and uncles how to hunt and kept them busy with fishing and other wild activities. My dad gave my two older sisters and I the choice of whether or not we wanted to participate in such adventures. I chose to do so and have been fortunate to go on multiple hunting trips, as well as countless fishing and hiking outings.

Goat hunting is special to our family and to my dad in particular. At 20 years old, Dad went on his first goat hunt with his brother, Bjorn, and another close friend. It was important to him that me and my sisters each got to experience our own goat hunt. Each of our adventures were different and significant in their own ways. In the fall of 2022, when I was 14, I went on my first mountain goat hunt. I was following in my older

sisters’ tracks, both of whom made their own goat hunt with our dad when they were similar ages. It was my turn.

MY DAD AND I left in mid-September on a rainy and foggy morning. I was feeling downcast, as the idea of spending a week sitting in the wet alpine was not very enticing. We boarded a ferry out of Juneau to a small outlying community. Rain spun sideways along the deck and I watched the whitecaps pass by from atop the boat. As we drew nearer, my mind started to race as I thought about the possibility of earning my own mountain goat.

We disembarked from the ferry and drove a short way before parking along the side of the road. After checking that we had all the essential supplies and tools, my dad and I started up the mountain. The light rain wasn’t hard enough to require a jacket, so we trekked up in our T-shirts.

The fog was rolling in and out lower on the mountain and at about 2,000 feet we crossed into a barrier of solid white. Visibility was practically nonexistent, but my excitement hadn’t worn off yet.

We set up camp at 3,200 feet and changed into warmer clothes. I arranged the tent as my dad left to stash our food. We lay in our sleeping bags, listening to the crying of the wind before getting up a while later to prepare dinner. I slurped down my freeze-dried chicken and rice and felt like I was stuffed inside a giant ping pong ball surrounded by all white. After 45 minutes of staring into the abyss, we headed off to bed.

THE NEXT MORNING, WE woke up early and were greeted by fog once again. I thought of my sister, Adella, who last year had spent most of her goat hunt in the fog. She and my dad spent multiple days waiting for a weather window, occasionally hiking out along the ridge to watch the fog roll by. They were snowed on and had extensive amounts of wind and rain. I slipped into my sleeping bag and lolled off for a short while.

My dad and I took turns throughout the day looking out of a small opening in our tent into the endless white. Rays of sunshine occasionally peeked through, and I hoped desperately for a clear patch. In the late afternoon, we were discussing whether or not we should drop down some elevation to try to get below the clouds. I was hesitant to go bushwacking that late in the day, and my dad agreed that it would be a tactic we’d reserve for later in the hunt. But since we had stayed in our tent all day, we decided to go out and stretch our legs.

A few minutes after emerging, blue sky peered out above us and the adjacent mountain was clearly visible as the fog to the east started to shift away. We looked up the ridge, which was clear enough to see part way up, and rushed to grab our packs and gun.

I felt exhilarated as I trailed behind my dad and tried to make my steps as quiet as possible. We hiked up to 3,700 feet before cutting off to the left of the ridge. While traversing the uneven slope, I gazed around in awe at the beautiful Alaskan wilderness. The alpine was filled with the red and orange colors of fall.

“Do you see that spot over there?” my dad whispered, pointing to a vague area. I nodded and peeked over his shoulder to get a better look. “That is where Kiah (my oldest sister) shot her goat.”

I smiled as we pressed on through the haze and crossed over a small section of rocks. My dad bent over and picked up a tuft of goat hair, placing it in my hand before walking on. I tucked the fur into my backpack pocket for luck and raced to catch up. We crested a small slope before abruptly stopping. I heard a strange sound: the whispering of shaking fur and falling rocks. Whipping my head around, I spotted the off-white hair and black horns of a goat dashing out in front of us. I would later tease my dad that I saw the goat before he did. I dropped down as fast as I could, slinging my pack in front of me to use as a rest. My dad hastily handed me the gun and I peered through the scope as the goat crested the knoll, pausing to glance back in our direction.

“It’s a billy,” I breathed, looking at the slow curving of the horns and thick bases.

BEFORE COMING ON THIS hunt, my dad had taught me the importance of trying to shoot a billy over a nanny. While killing either is legal, not shooting a nanny can help the goat population considerably in the long run. Nannies start mating when they are 4 to 5 years old; they tend to only give birth to one kid at a time. This can make the mountain goat population vulnerable, which is why I believe it is important to try and shoot a billy.

I shoved the gun at my dad to confirm that I was correct. He examined the goat before handing the gun back over.

“Yep, it’s a billy. It’s your shot,” he whispered.

I took a deep breath and settled the gun on my pack. I lined the scope up, my finger shaking on the trigger. My dad whispered encouraging words as I took another quick breath. The goat started walking and I followed it with my gun, pressing the stock of the rifle against my shoulder. The goat turned again and gazed back, the wind blowing steadily in our faces and not giving away our scent.

With one last movement, I found the shoulder and squeezed the trigger. The goat jumped up in the air, stumbling a few feet before disappearing behind the edge of the ridge. I looked over at my dad, then we gathered our packs and prepared for the upcoming search for the goat.

We scrambled over a boulder field to where the goat disappeared and peered down the hillside. The goat was crumpled on the steep slope – only yards from an intimidating cliff. “Congratulations,” my dad smiled, then gave me a high five. “You just got your first goat.”

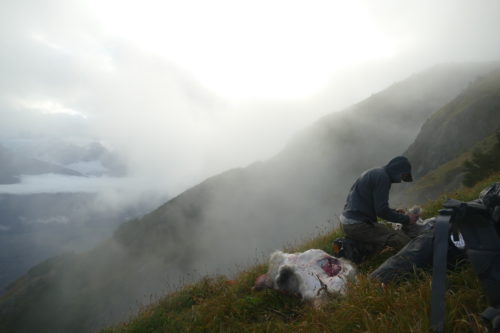

I was elated and smiled as we slipped down the mountainside and set our packs down on a flat spot before assessing where we should move the goat. Clipping on crampons, my dad and I set to work dragging my goat to a safer place to process.

After securing the goat, we got our gear and started cutting up the animal. I have been a part of several Sitka blacktail deer harvests but never a goat. I watched my dad carefully as he taught me how to properly clean the animal in order to collect as much meat as possible. I stopped a few times to gaze at the mountains around me as the fog started to close in and the sun began to dip below the horizon.

We assembled our meat into game bags and began our hike up the steep alpine rise. The sun had gone down and the fog settled low on the mountains, which made it hard to see where we had come from.

I watched nervously as my dad used his compass to find our way back to camp. I breathed with relief when we arrived at our campsite. The goat’s meat and horns were placed away from our tent so as not to attract bears. We celebrated the day with Snickers and gummies while preparing dinner. My dad fried up the goat’s heart in the Jetboil and threw it into our freeze-dried meals.

THE NEXT MORNING, WE gathered our gear and meat and said goodbye to the mountain. As we hiked down, the leaves from deciduous trees littered the ground and a cool autumn breeze whistled by.

I thought about my sisters and what they had experienced on their goat hunts. I felt so lucky to have the opportunity and was thankful for the goat meat. We reached our car safely and gazed up at the mountain. About 15 goats dotted the slope above, milling around on the lower parts of the cliffs.

I watched my dad as we packed up and wondered how he had felt after he shot his own first goat. Even through the fog and rain, there was no doubt that our time on the mountain was gratifying and memorable. Now I understood why he loved goat hunting so much. ASJ

Editor’s note: Braith Dihle’s older sister Kiah wrote about her own hunting experiences in the July 2016 issue of Alaska Sporting Journal.