Book Excerpt: Riding Bristol Bay’s Crimson Wave

From the first time he set foot in Alaska – in the 1970s, after accepting employment opportunities with Rep. Don Young and Sen. Ted Stevens, Washington, D.C. movers and shakers who represented the Last Frontier in Congress – Bill Horn felt he had arrived in a special place.

Horn, who went onto an intriguing career in both politics and law, is also a passionate outdoorsman who became particularly smitten by the endless supply of migrating salmon and hungry

trout in Bristol Bay. The author who says he’s “about 95 percent retired” has published works that include fishing in Florida – he lives in the Florida Keys with his wife Jeannette – and ruffed grouse hunting.

“Each year 60 million or more wild salmon pour into the Bay to fight their way upstream past nets, bears, swirling rapids, cascading waterfalls and anglers in lake and river systems with extraordinary names – Iliamna, Kvichak, Naknek, Nushagak, and Ugashik – that set anglers’ hearts aflutter,” Horn writes in his new book that pays respect to Bristol Bay, its remarkable salmon runs and other species that inhabit these waters. “It is the last place on Earth where great wild salmon runs remain the dominant force shaping not only the ecology, but human enterprise too.”

Horn cares just as much about protecting the watersheds of Bristol Bay – he spent time during the Reagan administration working on Alaska projects with the Department of the Interior – as he does catching the region’s fish.

The following is excerpted from The Crimson Wave: Sockeye Salmon, Rainbow Trout, and Alaska’s Bristol Bay, published by Stackpole Books.

BY BILL HORN

Rivers and streams littered with salmon carcasses is a sure sign of seasonal change. The short Alaska fall has arrived, with the long, cold, dark winter not far behind. Daylight grows shorter by about six minutes each day. By October 1, the sun doesn’t rise until nearly 9 a.m. – thanks, daylight saving time!

Daytime highs in September drop to the mid-50s, and there will be more rainy days than sunshine. Powerful storms packing mean winds and driving rain blow in from the North Pacific and Bering Sea. Fall anglers must be prepared, psychologically and physically, to get weathered in, and for the conditions when they can get out on the rivers.

Fall weather is no joke, and smart anglers should carry some basic survival gear in case they get stranded overnight. A 1-gallon ziplock bag with a lighter, waterproof matches, firestarter material, a chocolate bar, a small water filter, a space blanket and a Leatherman tool will let you stay relatively warm, dry, watered and fed. The ensemble fits easily in the back of most fly-fishing vests. And don’t leave your rain jacket unattended on a riverbank on an apparently warm, dry day. Porcupines will chew on it and curious bears will carry it off, leaving you unprotected when unpredicted rain or snow blow in.

The September 11 terrorist attacks demonstrated the need to carry some emergency supplies. That morning, the fly-out lodges dispatched their floatplanes loaded with guides and clients for another day of fishing.

Anglers got dropped off, and plans were made for a late-afternoon pickup and return to the lodge. By midday, the FAA had shut down U.S. airspace, including Alaska; all planes were grounded. Anglers and guides, totally out of touch in the Alaska bush, assembled at their prescribed pickup spots and waited and waited. One bush pilot friend was unaware of the grounding orders and took off to pick up waiting clients. An F-16 jet swooped down, stood off his wing, and gave him an emphatic thumbs-down sign. He landed at a nearby village and was stuck there for days.

As the lawyer for a number of the lodges and pilot services, I started getting frantic satellite phone calls about grounded planes and stranded clients. It took a major effort by Alaska’s congressional delegation to get the FAA and the U.S. Air Force to let the lodges and bush pilots go out and pick up the clients.

Some spent three nights out with no knowledge of what had happened. Many of the survivors of this ordeal reported they believed nuclear war had erupted and it was all over. The sky was empty of aircraft except for military jets streaking back and forth at very high altitudes.

TIME FOR TROPHY RAINBOWS

Despite often marginal weather, the sockeye dieoff and the onset of fall can produce spectacular fishing, especially for trophy rainbows. Around Iliamna Lake, the biggest rainbows move into tributaries like Lower and Upper Talarik Creeks, Gibraltar Creek, the Newhalen River and down into the Kvichak. In nearby Katmai Park, big ’bows are on the move in the Kukaklek Lake headwaters: Moraine Creek and the Battle River.

Among these, Lower Talarik gets the most headlines. A modest, low-gradient stream, it flows through a series of small lakes and ponds into the north side of Iliamna Lake about 20 miles west of the village of Iliamna.

Noticeably big rainbows move in during September and October, when it becomes a prime place for trophy fish to 10 pounds or more. Lodges and anglers literally fight to get on good stretches of the creek, like the famous Rock Hole, where a big out-of-place rock sticks out like a sore thumb. Such is the creek’s fame that even 40 years ago area lodges made special plans to fish it. Only a few floatplanes can safely land and tie up there, so it was a daily race to see who could get there first and secure one of the spots. Lodge guests were rousted from bed in the predawn dark and jammed into the plane at first light. That still goes on. I’m not a big fan, even though I’ve caught a couple of good rainbows there.

Contemporary anglers enjoying Talarik’s trophy ’bows are unaware that public access to the creek was almost lost 30 years ago. A mostly unknown Native allotment application filed in 1971 came up for adjudication by the federal government (up until 1971, Native Americans were able to file applications for ownership of up to 160 acres of federal land if the applicant could demonstrate certain levels of customary use of the parcel). The state typically tried to track applications/adjudications that had possible impacts on Alaska Statehood Act land selections or public fishing and hunting access and raise timely objections that could get resolved before final approval of an allotment application. However, the state missed this one until it was on the cusp of approval.

Anglers and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game were upset because the allotment covered most of the lower end of Lower Talarik, including the famous Rock Hole. Mac Minard was tasked with trying to resolve the dispute at the eleventh hour. As he recounted to me, he was in a real bind: On one hand, a respected Native elder had filed the claim, and on the other, the state had failed to contest it in normal fashion (i.e., work out boundary and access issues), so the only apparent remaining option was to flatly oppose the claim. Mac pictured the damning headline: “ADFG seeks to kick tribal elder off his land to expand public fishing access.”

Things were looking grim for Lower Talarik anglers. Fortunately, Minard got in contact with the Alaska Nature Conservancy and together went to work negotiating an arrangement with the claimant, Mr. Anelon. He was a sincere and thoughtful man interested in preserving his traditional use of the land for hunting, fishing and berry picking without running off the public. A complicated deal was struck in which the land would be transferred to the state of Alaska subject to a conservation easement to protect Mr. Anelon’s uses, traditional uses by other local Natives, and angler access. Orvis played a critical role in soliciting and donating funds for the transaction. Angling artist Adriano Manocchia did a painting of the creek to commemorate the deal. Mac considers it one of his finest professional moments. And every angler who enjoys chasing Lower Talarik’s trophy ’bows should take a moment and tip his or her hat to Mr. Anelon, the Alaska Nature Conservancy, Orvis, Mr. Minard and Mr. Manocchia.

BRISTOL BAY CONSERVATION ROYALTY

Jim Repine was “Mr. Alaska Fly Fishing” in the 1970s and 1980s. A larger-than-life Falstaffian character, during his heyday he hosted an Alaska fishing television show, edited Alaska Outdoors magazine, wrote four books on Alaska fly fishing and was a ubiquitous presence at Lower 48 fly-fishing shows. I met Jim in 1981 and had the pleasure of fishing with him (and his dog) throughout the 1980s. A genuinely great guy, he never let his 49th state fame go to his head. On a fishing trip to Chile, he met a widow, fell in love, married and moved south. Later they ran Futaleufu Lodge deep in the Chilean Andes. Jim succumbed to brain cancer in 2009.

Repine recognized the substantial economic value of well-managed recreational fisheries and fervently believed Bristol Bay could be a showplace for how to integrate and manage conservation, commercial fishing and sport angling. He would have been a loud voice for protection of Iliamna Lake and its fish rich environs from the proposed Pebble pit mine.

Bristol Bay’s conservation story must always include the late Jay Hammond, former governor of Alaska (1974–1982). Jay was a Marine Corps fighter pilot in World War II flying with the famous Black Sheep Squadron in the Pacific. He moved to Alaska after the war to become a bush pilot and was quickly entranced by the Bristol Bay country. He homesteaded on the shores of Lake Clark and married a lovely Native woman, Bella Gardiner. Quickly attracted to local politics, he was elected to the Alaska legislature in 1959 and served there until 1973. From 1972 to 1974 he was also mayor of the Bristol Bay Borough. Designation by the state of Alaska of the Bristol Bay Fisheries Reserve as well as five important salmon-related critical habitat areas occurred in 1972, with Jay providing key leadership.

He was elected governor in 1974, as a Republican, and barely reelected in a wild race in 1978. Challenged by former Alaska governor and Secretary of the Interior Wally Hickel, Hammond prevailed by 89 votes. Jay was quick with jokes about his “landslide” win and “mandate” from the voters. A burly, bearded and affable man with a great baritone voice and deep principles, he was central casting’s perfect vision of an Alaska governor. One of his books is titled Tales of Alaska’s Bush Rat Governor.

During the Alaska lands battle in Congress (1977–1980), Jay proposed creation of a special federal-state cooperative conservation zone around Lake Iliamna, including the famous rivers that feed into it. As previously noted, the land ownership of the area was considered too fractured for designation of a purely federal or state conservation area. The congressional leadership of that era wasn’t interested but did open the door in Title XII of the 1980 lands bill, ANILCA, to future creation of such a unit. Hammond’s immediate successors weren’t interested either, and by the time the state leadership cared again, the federal administration had changed and did not.

I had the good fortune to work a lot with Jay, and the last time I saw him we shared the stage in 2000 along with former president Jimmy Carter and his Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus at a University of Alaska event on the 20th anniversary of the signing of ANILCA. Jay passed away at Lake Clark in 2005 at 83 years old. ASJ

Editor’s note: Bill Horn’s other books include Seasons on the Flats: An Angler’s Year in the Florida Keys and On the Bow: Love, Fear and Fascination in the Pursuit of Bonefish, Tarpon and Permit. Ordering information for The Crimson Wave can be found at stackpolebooks.com/books/9780811772433.

Q&A WITH AUTHOR BILL HORN

Alaska Sporting Journal editor Chris Cocoles caught up with The Crimson Wave author Bill Horn, who talked Alaska passions, conservation concerns and the trophy trout that have gotten away.

Chris Cocoles Congratulations on a great book that captures the spirit of Alaska and Bristol Bay’s fishing scene. Was this your first project that focused solely on the Last Frontier?

Bill Horn Yes, it is my first writing venture about Alaska that wasn’t related to my government service or legal practice, and definitely more fun to write. The idea of telling the Bristol Bay angling story via the life cycle of the sockeye was born long before I wrote my books on saltwater flats fishing and ruffed grouse hunting, but I wasn’t sure I had the ability to actually write a book that would do justice to the Bay region. Guess I “tuned up” with the others so I could do right by the sockeye, rainbows and the 49th state!

CC Your Alaska ties date back to 1977 when you began to work with Rep. Don Young and Sen. Ted Stevens. How did that come about?

BH The connection really started in 1972 when I was working part time – I was still in college – for Trout Unlimited. We made a pitch to the U.S. Department of the Interior about conserving the Iliamna Lake and river systems for the benefits of salmon and trout. That was my first real exposure to Alaska issues. Two years later I was a young congressional staffer and ended up working on the Alaska pipeline bill when I met Don Young, who had just been elected to the House. In early 1977, the House was about to wrestle with the big Alaska lands bill and the proposed Alaska natural gas pipeline. Don had just become the ranking Republican on the new Alaska Lands subcommittee and had the right to hire a staffer for it. He remembered me from the oil pipeline fight and offered me the subcommittee slot – I jumped on it.

I spent the next four years consumed with the giant lands bill that became the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980. Got to travel all over Alaska during those years, including my first trips to Bristol Bay for hearings and meetings in Dillingham, King Salmon, Katmai, Togiak and Port Alsworth. When the bill would leave the House and go to the Senate, Don detailed me over to Sen. Stevens to work on the bill on that side of Capitol Hill. I was one of two staffers who had the privilege of working on ANILCA on both the House and Senate sides.

CC From a pure fishing standpoint, did you have a welcome-to-Alaska-moment?

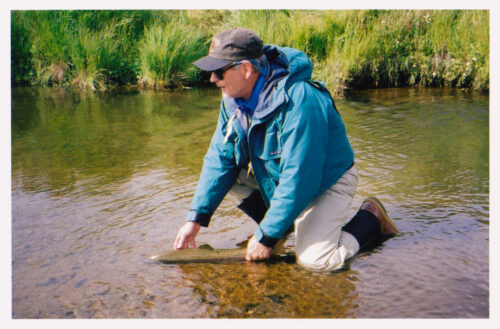

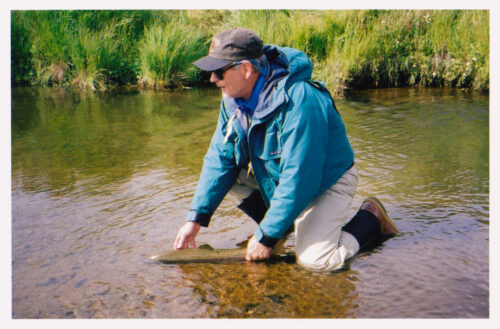

BH Absolutely. The subcommittee was conducting hearings all over the state in 1977 and we ended up in King Salmon. The National Park Service arranged for an overnight stay at Brooks Camp in Katmai and I stole a couple of hours to get on the Brooks River. It was full of bright red prespawn sockeye, and I was told the rainbows would follow the salmon. Found my way to the river, keeping a wary eye open for brown bears, and started pitching a No. 6 Polar Shrimp. It was drifting/swinging along when it got grabbed, and a hot rainbow raced off, leaping en route. Landed this bright, hard, red-striped, 16-inch fish and couldn’t believe that a kid who had grown up in Florida and New Jersey was holding and releasing a bona fide Alaska trout in this incredible place. I was hooked on the 49th state.

CC When you worked as deputy undersecretary for the Department of Interior during the Reagan administration, Alaska was one of your focuses. Did that give you even more perspective about how special the state’s natural resources are?

BH The great privilege of traveling all over the state during the lands bill battle had already impressed on me how special and unique Alaska was and is. Then the opportunity to direct implementation of the bill, and the major compromises it represented and codified, was a continuing education about the Great Land. A seminal moment for me was a 1981 return to King Salmon with then Alaska Gov. Jay Hammond. Jay, who was from the Bristol Bay region, wanted to impress on the new Interior Department leadership the unique value of the Bay region. I spent a full day with him and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game Bay personnel getting briefed at length about the sockeye run, how it’s managed and how the state was struggling to restore the runs that had been decimated by federal mismanagement in the 1950s and foreign overfishing during the ’60s and ’70s. It was an incredible eye-opening experience and the lessons learned that day, and later, helped me in the fisheries conservation and management business when I was chairing the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, helping negotiate the U.S.-Canada Pacific Salmon Treaty, and serving on the boards of private fishery groups such as the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust and Trout Unlimited.

CC It looks like you’ve fished all over the place. But what makes the Alaska experience so unique?

BH I need a whole book to answer this question! The “time machine” quality of Alaska is unique – a chance to be part of a complete fish-driven natural system in a vast, wild setting. You see millions of salmon return to the Bristol Bay rivers and lakes supporting a vibrant ecology, including trophy rainbow trout, bald eagles and brown bears to name a few of the other species dependent on the sockeye.

In contrast, throughout the Lower 48 states and elsewhere, we struggle to hold on to the remnants of great natural fisheries, where the fish are all too often an afterthought standing at the back of the line behind water supply for agriculture and cities, electric power generation and land uses incompatible with healthy streams, rivers and estuaries.

CC I can tell in reading through the book that you have a real admiration for salmon and the life cycle that those remarkable fish run through again and again. What has that meant to you to be a part of fishing for Alaska’s salmon?

BH Following on from what I said before, you stand in a Bay region river during the sockeye run and you’re in the middle of a great pageant of life. There is life and death being played out on a grand scale above the water and below. For anglers and others who appreciate aquatic habitats, this is the Serengeti of fish. Becoming part of this, as an angler, touches those remnant parts of us connected to natural cycles. Those connections are ever more important in a modern, urbanizing, crowded world.

CC You also write a lot about trout fishing in the Last Frontier. Can you share some rainbow memories in Alaska?

BH Odd as it may seem, my most vivid memories are of big rainbows that I’ve lost. As told in the book, I have never been able to catch the trophy 30-inch/10-pound rainbow trout. A couple have reached 29 inches and the damn ruler wouldn’t stretch to give me 30. The first “big one that got away” was a monster on the Naknek one cold, rainy late-August day. It leapt around the boat, letting us get repeated good looks before racing off, pulling the hook and breaking my heart.

Years later, we were creeping around Funnel Creek sight fishing for big single rainbows. One in our group spotted a “kahuna” – we all agreed it was 30 inches plus – in a tight lie that was best fished by a left-hander: me. The dark-green-backed trout was below a willow tangle and the key was to hook it and get it going downstream away from the line-breaking snag. Crawled into casting position and stayed on my knees. On the fifth cast, the big trout drifted right, I saw the white mouth open and it took the bead. Set the hook, pulled hard to turn the fish downstream and scrambled up. For a minute I got the fish coming my way and hope flared – briefly. Mr. Trout promptly regained his bearings, and bulldogged upstream heading for the snag. I put on major pressure – pretty major, as I was using 2x tippet – but the trout shook it off and bored into the snag, shearing the leader. In the words of Snidely Whiplash, “Foiled again.”

CC This book also seems like it’s an ode to Bristol Bay. Is that a special place to you?

BH The Bay and its river/lake systems are a super special place for me. It has everything that makes Alaska special: sparkling jagged mountains, smoking volcanoes, deep mountain passes lined with blue hanging glaciers, giant lakes, big sweeping rivers along with intimate streams, millions of salmon, great trout, the magnificent brown bears, traditional villages and an entire culture tuned into the fisheries. What’s not to like?

I’ve also been able to become friends with many of the locals and poke around a lot of little-visited corners of the region. An incredible landscape, fish and wildlife beyond compare and wonderful people is an unbeatable combination.

CC You make a passionate argument to protect Bristol Bay’s salmon runs and not risk implementing the Pebble Mine project. While you acknowledge that you’ve been a proponent for mining and drilling in other areas of Alaska, do you just think when it comes to what Bristol Bay produces, it’s not a gamble worth taking there?

BH Bristol Bay contains an irreplaceable wild salmon fishery. There is a complete three-legged sustainable economy built on that last, best salmon run: a commercial fishery (boats and set netters), a traditional subsistence fishery, and an angling industry. I got taught, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” and given the management success represented by sockeye runs topping 70 million fish, it ain’t broke. It makes no sense to jeopardize this last, best wild salmon run and a working sustainable economy for the short-term benefits of high-risk mining straddling the headwaters of the Iliamna/Kvichak and Mulchatna/Nushagak systems.

One other factor deserves consideration. The fight is not about just one mine project. If Pebble is built, a vast infrastructure of roads, pipelines, electrical facilities, ports, housing and other facilities will be created. There are other mineral deposits in the area that are not big enough to carry the costs of such infrastructure. But if Pebble is built, these smaller deposits can piggyback on the Pebble infrastructure. The result will be a full-fledged mining district – with multiple operations in the area – not just a single project. That’s plainly too much of a gamble.

CC Do you have a favorite Bristol Bay/ Alaska fishing area that you could be content spending every fishing experience for the rest of your life and be satisfied with just casting there? BH As much as I adore the Katmai and Wood River/Tikchik areas in the Bay, I’d hate to be confined to one fishing spot. Alaska rainbows are great – in my top four fish – but I’d hate to give up on my saltwater flats pals: the tarpon, bonefish and permit. If you read my flats books – On The Bow and Seasons on the Flats – you’ll know why.

CC And on that note, Alaska has so many angling opportunities, so is there a place or maybe a species you haven’t fished at/ targeted that’s on your bucket list still?

BH Twice I had trips to pursue sheefish canceled, and it sure would be fun to put one of them on my lifetime “catch list.” And a few friends have tried to get me to try for steelhead by Yakutat, on Kodiak and down the Alaska Peninsula. Maybe one of these days.

CC Do you look back now and think back to 1977 and say that your experiences in Alaska changed and impacted your life?

BH Absolutely. A huge part of my professional life has been connected to Alaska and I cannot imagine what else could have taken that much of my time, attention and passion. Nothing else that I know of would have been anywhere near as much fun or as endlessly interesting. The chance to be a natural resources/ wildlife professional and lawyer was a dream come true and was the result of my introductions to Alaska all those years ago. I have been extraordinarily fortunate and privileged to have been able to combine my avocation and my professional life. God forbid that my career was spent doing divorces, car wrecks, wills, real estate closings or tax law! ASJ